To be born a woman in India. Foeticide and infanticide: origins, consequences and solutions.

Source : www.bynativ.com

May 26, 2021

Written by Jérémy Terpant

Translated by Jessica Norbert

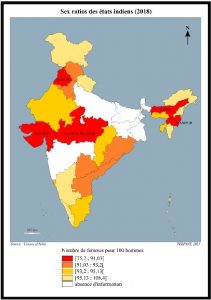

In 1990, the Indian economist and philosopher Armatya Sen alerted to a phenomenon mainly affecting girls: the selection of births; leading to a significant demographic imbalance. By that time, there were already 100 million women missing in Asia[1]Amartya Sen, « More than 100 millions women are missing », The New York Review of Books, 20/12/1990, available at: … Continue reading. India is particularly affected. Even though there are slightly more boys than girls born in the world, that simple sex ratio does not explain such a phenomenon since, for example, “the status of a brahmin woman is more enviable than that of a man of lower cast[2]Kamala Marius, « Les inégalités de genre en Inde », Géoconfluences, 2016, available at: … Continue reading”. Despite a constitution that says banning all discriminations (gender, caste, religion…), this country is experiencing high inequalities, and discrimination against women is omnipresent: in the early 2000’s, 36 million[3]Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparu, La Découverte, 2008 women were missing, in 2018 that deficit reached 63 million[4]Shannah Mehidi, « L’Inde manque de 63 millions de femmes », Le Figaro, 31/01/2018, available at: … Continue reading.

To have a daughter in India, is to foresee additional costs, those of the dowry and the wedding. It is also risking dishonoring the family and being excluded. Thus, many families prefer to eliminate the girls and hope to have a boy. The country is facing a strong masculinization of the population, to such an extent as to render the marital market saturated. The women are paying a heavy price with an increase of sexual violence and commodification of wives. To address this, the Indian government is multiplying awareness-raising campaigns but seems nonetheless to be overwhelmed by the magnitude of the phenomenon. In parallel with the public authority, influential figures, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are acting to raise awareness in the country to the issue of women.

This writing will focus on the issue of foeticide, the act of killing a baby before its birth, and infanticide, the act of killing a newborn before it is declared, which are rampant in India. With the development of the ultrasonography in the 1980’s, the sex-ratio imbalance is accentuated as shown by the figures previously mentioned: we observe that there is a “lack” of almost twice as many girls in 2018 than in the early 2000’s. Several questions thus arise. What are the consequences of infanticides and foeticides for the women but also for the Indian society as a whole? What actions are being taken to address this?

Having a daughter in India, a burden?

The woman, not working in the fields for example, is not considered a productive society member. The Indian quote according to which “raising a daughter amounts to watering the garden of the neighbor” perfectly illustrates this heritage: having a daughter is taking care of her, and therefore spending, so that she devotes herself to her in-laws after her marriage. Therefore, it is preferable to have a boy, considered a long-term investment. As a result, he will be better nourished and better educated.

Having a daughter in India is expensive, especially since the average salary remains relatively low. There is first the wedding which, in this country, is a “symbol of social status in a now very materialistic society, where only money matters[5]Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparu, La Découverte, 2008” according to Soubhagya K. Bhat, prescribing doctor of the country’s family planning. This is why for modest families, having a girl often amounts to being heavily indebted, when we know that, according to Donna Fernandes[6]Emblematic figure of the fight for Women’s Rights in India, Donna Fernandes has been working on gender inequalities for over than 30 years. She participates in the creation of Vimochana., a wedding costs at least 1 500 000 rupees (20 500$)[7]Ibid..

The dowry constitutes yet another burden imposed on the bride’s family. If historically, the dowry was handed from the husband to the wife, the trend has reversed to become a compensation offered by the family of the bride to the family of the husband who will have to “take charge” of her. With the economic development of the country, the dowry grows more and more in magnitude and even becomes a criterion: some families, if they have the choice between two women, will take the most “profitable” one. Although legally prohibited, this practice remains rooted in the custom and knows many drifts: even after the marriage, and the dowry paid, it happens that the in-laws keep asking for money to the bride’s family. Bénédicte Manier, journalist and specialist on India, explains in the book “Quand les femmes auront disparu” that in case of refusal, some families do not hesitate to attack the young bride: the latter may be harassed, beaten, or even killed. The bride’s family may then be forced to give into the blackmail to protect their daughter.

These reasons explain the increase of infanticide in India. From the late 16th century, the British arriving in India, had noticed this phenomenon to the point of legally banning it from 1870. Nonetheless, these habits remained during the 20th century and still today. Traditionally, the baby is confined in a jar during a certain ritual. Today, many methods are used: some young girls are suffocated in plastic bags, others are drowned, or else poisoned. It is however more frequent to see an infanticide qualified as “slow” or passive when the girl is victim of negligence (lack of care, lack of food…). Finally, it is important to emphasize that many girls are abandoned at birth: In India, 90% of the abandoned children are said to be girls[8]Ibid..

Lastly, let us mention the issue of abortion which continues to grow in India. According to the NGO Saheli, the national production of ultrasonography equipment increased by 3 300%[9]Laxmi Murthy, Vineeta Bal, Deepti Sharma, « The Business of Sex Selection : the ultrasonography boom », Saheli Women’s Ressource Center, 2004 between 1989 and 2003. In India, it is very frequent that these devices are used to determine, as quickly as possible, the Sex of the foetus. The result of this examination will determine its fate.

Abortion then becomes a solution to not giving birth to a girl. Therefore, observing the law, public hospi

tals in the country prohibit revealing the Sex of the foetus in order to counter selective abortions. The Sex of the foetus being visible from the 16th week, and the legal practice of abortion being until 12 weeks, many women then turn to much less regarding private clinics. In 2006, The Lancet estimated at 500 000[10]Prabhat Jha, Rajesh Kumar, Priya Vasa, Neeraj Dhingra, Deva Thiruchelvam, Rahim Moineddin, « Low male-to-female sex ratio of children for in India : national survey of 1.1 million households », The … Continue reading the number of female foetus victims of foeticide in India.

A scourge with heavy consequences, towards a commodification of the woman?

A real scourge, the selection of births generates many repercussions. First, the marital market is more than saturated. Today, faced with the shortage of women in India, many bachelors encounter difficulties to find a wife. Yet, not marrying is not having children – or rather sons – therefore no heirs able to take over the family property. This disturbance of the marriage market is also heavy with consequences for the women.

The young men’s celibacy leads to frustration which contributes to the increase of violence against women within a society where they are already omnipresent. Despite an anti-rape law, passed in 2013, not only does the rape culture persist, but is also budling up a phenomenon of women and children trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation, consequences of male frustration felt due to the difficulty of finding a wife. Forced prostitution, form of sexual exploitation, mainly affects women, often young girls, from the caste of the untouchables. Some are victims of traffickers, others are taken. Families can also play a role in the trafficking of women and girls for the purpose of sexual exploitation.

This commodification of the woman also applies in the context of marriage. Faced with the situation, a new market has emerged: that of the wives. Middlemen, intermediaries, offer finding a wife to young bachelors. These intermediaries then travel through the poorest regions of the country where they buy women, often young girls, whom they later sell to their clients. Thus develops a real black market of the woman in which prices vary according to “the quality” of the latter: the more the woman is “noble”, that is to say has acquired good education or else comes from a higher caste, the higher the price will be. Although it is difficult to have statistics and information on the rates, Bénédicte Manier explains that the price of a wife can range from 5 000 rupees (56€) to 100 000 rupees (1 129€)[11]Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparu, La Découverte, 2008.

Faced with the lack of women, some families who do not have the means to resort to these middlemen then turn to an ancient tradition in India: polyandry. Defined as a “form of matrimonial regime that allows the legitimate union of a woman to several men[12]Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales, available at: https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/polyandrie”, it allows a woman to marry one – or more – brother(s) of her husband. Extremely rare, some specialists fear to see this ancestral legacy grow to face the current context. Although carried out under a forced arrangement by the in-laws, polyandry seems to be tolerated and accepted in India.

Putting an end to infanticide and foeticide in India, what solutions?

Faced with foeticide and infanticide, the Indian government has implemented measures. While it is difficult to imagine a limitation of the access to abortion, not only because it constitutes an inalienable human right for women to dispose of their bodies, but also because restrictions would increase clandestine abortions, Donna Fernandes advocates better control of the ultrasonography to avoid the previously mentioned drifts. That is why the Indian government has created several laws. In 1978, the use of amniocentesis[13]Medical procedure during which a small amount of amniotic fluid is taken. After analyses, the amniocentesis enables a karyotype (photographic representation of chromosomes), and thus to … Continue reading are limited, only in public hospitals and in case of genetic disease. In 1983, the government banned the use of ultrasonography to know the Sex of the foetus. In 1994, gender-selective abortion was outlawed. Nevertheless, these measures introduced in the Indian legal arsenal are poorly applied since many families turn to clandestine or private clinics, given the fact that the sanctions are minimal compared to the economic gains of this market.

The action of the government also involves campaigns to fight against foeticides and gender inequalities (public displays, television programs, awareness-raising actions at more local scales). Let us mention here the campaign “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” launched by the central government in some states such as Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand or Delhi. Dated back to 2015, it aims to protect young girls and, more broadly, to reduce women-men inequalities. It is in that context that the Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, called “No longer abort your girls[14]Pauline Rouquette, « Malgré les efforts des autorités, l’avortement des filles reste pratiqué en Inde », France 24, 07 July 2019, available at: … Continue reading ». Financial aid is emerging as well to counter these phenomena. The state of Punjab, for example, provides grants to “girls protective” towns and villages[15]Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparus, La Découverte, 2008. The state of Delhi pays 5 000 rupees to families giving birth to a girl and then 3 000 rupees if she reaches a certain level in her studies[16]Ibid..

If the public authorities seem overwhelmed by the issue, the actions carried out by NGOs, or by certain influential celebrities are to be taken into account. Sania Mirza, Indian tennis player and UN Women regional ambassador for South Asia declared: “All of us who have been able to achieve great things must serve as example to women[17]UN Women, «Regional UN Women Ambassador Sania Mirza » (s. d.), available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/partnerships/goodwill-ambassadors/sania-mirza”. She knew well to use her notoriety to fight against this scourge with billboards in her effigy for the Punjab, bearing the slogan “Your daughter could be the next champion”. NGOs such as Vimochana[18]Launched in 1979, Vimochana fights against all forms of violence affecting women. Available at: https://www.vimochana.co.in/ are also fighting for the end of inequalities in India and violence against women (including foeticide). Others rely on the economic aspect by helping the women to find paid employment or by encouraging the girls to pursue an education in order to integrate more easily the labour market.

Moreover, it is today difficult for a woman to work in India, and even when she finds a stable job, she will be much less paid than a man. Promoting girls’ education to facilitate their integration of the labour market as well as achieving equal salary for women and men would therefore allow to limit the number of foeticide and infanticide. The woman would then be considered as a productive member of the society: her income could provide for the needs of her household. Likewise, legally a woman does not possess property. Yet, if a woman had the possibility of dispo

sing a capital, the dowry requested by the in-laws wouldn’t be as important anymore.

To end gender inequalities, India must work on enforcing the law and pushing forward the mores. The example of the dowry, which gets more and more expensive for the bride’s family, perfectly illustrates the work that is yet to be done on mentalities. Despite few rising voices, particularly among the Indian diaspora, this practice remains anchored in mores. There is strong social pressure around this question since, despite its prohibition, refusing to pay the dowry is taking the risk to not marry your daughter. It is however still difficult to envisage the end of that tradition, still strongly established in the “materialistic[19]Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparu, La Découverte, 2008” Indian society, according to the words of Doctor Soubhagya K. Bhat.

The Ipas Development reveals that 47% of the abortion that could have probably been performed in India between March 25th and June 24th, 2020, did not occur[20]Ipas Development Foundation, « Compromised Abortion Access du to COVID-19 », May 2020, Ipas Development Foundation, available at: … Continue reading.

If the government of the union seems determined to fight against these foeticides and abortions, this study highlights nonetheless that this decrease is mainly due to the health context (unavailability of abortion pills, difficult access to clinics…) and not to the various measures put in place, since the abortion rate has remained unchanged since 2015.

Conclusion

Even before their birth, girls are considered as burden in India. With the development of ultrasonography, and despite the interdiction of targeted abortions since the law of 1994, families have increasingly resorted to foeticide or infanticide, including “slow”, when it comes to girls. India, like a large part of Asia, is thus experiencing an over-masculinization of its society which render the marital market saturated. Then is developing a phenomenon of women and girls trafficking for the purposes of sexual exploitation and forced marriage.

Faced with this gender crises, the public authorities are responding by putting in place laws aiming to reduce foeticides, measures to help families who give birth to girls, as well as awareness-raising campaigns. Despite the established measures, the phenomenon continues to grow. In parallel with the action of the central government, the actions conducted by NGOs or Indian personalities are increasing.

Bibliography

Bone I. & PLOS One, « Inde : les avortements sur base du sexe restent légion », Institut Européen de Bioéthique, 08/26/2020, available at: https://www.ieb-eib.org/fr/actualite/debut-de-vie/avortement/inde-les-avortements-sur-base-du-sexe-restent-legion-1864.html

Census of India, « Chapter III – A brief analysis of data on registered births, deaths and infant deaths », Census of India, 2018, available at: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011-Common/CRS_2018/11%20Chapter%203.pdf

Ipas Development Foundation, « Compromised Abortion Access due to COVID-19. A model to determine impact of COVD-19 on women’s access to abortion », Ipas Development Foundation, May 2020, available at: https://www.ipasdevelopmentfoundation.org/publications/compromised-abortion-access-due-to-covid-19-a-model-to-determine-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-s-access-to-abortion.html

Kishwar M.,« When Homes Are Torture Chambers », India Together (s. d.), available at: http://www.indiatogether.org/manushi/issue110/vimochana.htm

Manier B., Quand les femmes auront disparu : L’élimination des filles en Inde et en Asie, La Découverte, 2008, 210 p., available at: https://www-cairn-info.ezproxy.univ-catholille.fr/quand-les-femmes-auront-disparu–9782707156242.htm

Manier, B., « Les femmes en Inde : une position sociale fragile, dans une société en transition », Géoconfluences, 03/24/2105, available at: http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-regionaux/le-monde-indien-populations-et-espaces/articles-scientifiques/les-femmes-en-inde-une-position-sociale-fragile-dans-une-societe-en-transition

Marius K., « Les inégalités de genre en Inde », Géoconfluences, 11/23/2016, available at: http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-regionaux/le-monde-indien-populations-et-espaces/corpus-documentaire/inegalites-genre-inde#:%7E:text=Les%20taux%20d’analphabétisme%20sont,ans%20contre%2032%20%25%20en%202008%20

Mehidi S., « L’Inde « manque » de 63 millions de femmes », Le Figaro, 01/31/2018, available at: https://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2018/01/31/01003-20180131ARTFIG00141-l-inde-manque-de-63-millions-de-femmes.php

ONU, « World Population Prospects 2019 », United Nations – Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019, available at: https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/

UN Women, « Regional UN Women Ambassador Sania Mirza » (s. d.), available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/partnerships/goodwill-ambassadors/sania-mirza

Rouquette P., « Malgré les efforts des autorités, l’avortement de filles reste pratiqué en Inde », France 24, 07/29/2019, available at: https://www.france24.com/fr/20190723-avortement-foetus-filles-inde-egalite-hommes-femmes-tradition-dot

Vella S., « Éthique et pratiques reproductives : les techniques de sélection sexuelle en Inde », Autrepart, 2003, available at: https://www.cairn.info/revue-autrepart-2003-4-page-147.htm?contenu=article

To cite this article: Jérémy TERPANT, “To be born a woman in India. Foeticide and infanticide: origins, consequences and solutions.”, 05.26.2021, Institut du Genre en Géopolitique.

References

| ↑1 | Amartya Sen, « More than 100 millions women are missing », The New York Review of Books, 20/12/1990, available at: https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1990/12/20/more-than-100-million-women-are-missing/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kamala Marius, « Les inégalités de genre en Inde », Géoconfluences, 2016, available at: http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-regionaux/le-monde-indien-populations-et-espaces/corpus-documentaire/inegalites-genre-inde#:~:text=Les%20taux%20d’analphabétisme%20sont,ans%20contre%2032%20%25%20en%202008%20 |

| ↑3, ↑5, ↑11, ↑19 | Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparu, La Découverte, 2008 |

| ↑4 | Shannah Mehidi, « L’Inde manque de 63 millions de femmes », Le Figaro, 31/01/2018, available at: https://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2018/01/31/01003-20180131ARTFIG00141-l-inde-manque-de-63-millions-de-femmes.php |

| ↑6 | Emblematic figure of the fight for Women’s Rights in India, Donna Fernandes has been working on gender inequalities for over than 30 years. She participates in the creation of Vimochana. |

| ↑7, ↑8, ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑9 | Laxmi Murthy, Vineeta Bal, Deepti Sharma, « The Business of Sex Selection : the ultrasonography boom », Saheli Women’s Ressource Center, 2004 |

| ↑10 | Prabhat Jha, Rajesh Kumar, Priya Vasa, Neeraj Dhingra, Deva Thiruchelvam, Rahim Moineddin, « Low male-to-female sex ratio of children for in India : national survey of 1.1 million households », The Lancet, 09/01/2006, available at: https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.univ-catholille.fr/science/article/pii/S0140673606679300 |

| ↑12 | Centre National de Ressources Textuelles et Lexicales, available at: https://www.cnrtl.fr/definition/polyandrie |

| ↑13 | Medical procedure during which a small amount of amniotic fluid is taken. After analyses, the amniocentesis enables a karyotype (photographic representation of chromosomes), and thus to determine the Sex of the foetus as well as to search for genetical diseases such as trisomy 21. |

| ↑14 | Pauline Rouquette, « Malgré les efforts des autorités, l’avortement des filles reste pratiqué en Inde », France 24, 07 July 2019, available at: https://www.france24.com/fr/20190723-avortement-foetus-filles-inde-egalite-hommes-femmes-tradition-dot |

| ↑15 | Bénédicte Manier, Quand les femmes auront disparus, La Découverte, 2008 |

| ↑17 | UN Women, «Regional UN Women Ambassador Sania Mirza » (s. d.), available at: https://www.unwomen.org/en/partnerships/goodwill-ambassadors/sania-mirza |

| ↑18 | Launched in 1979, Vimochana fights against all forms of violence affecting women. Available at: https://www.vimochana.co.in/ |

| ↑20 | Ipas Development Foundation, « Compromised Abortion Access du to COVID-19 », May 2020, Ipas Development Foundation, available at: https://www.ipasdevelopmentfoundation.org/publications/compromised-abortion-access-due-to-covid-19-a-model-to-determine-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-s-access-to-abortion.html |