Gender violence towards Uyghur women :

where does transnational advocacy stands?

27.08.2020

By Manon Cassoulet-Fressineau

On July 20th 2020, the denunciation of the Uyghur oppression perpetrated by the Chinese government was revived by an investigation published in the New York Times, accusing China of forcing Uyghurs to produce surgical masks destined to global export[1]Muyi Xiao, Haley Willis, Christoph Koettl, Natalie Reneau and Drew Jordan, “China Is Using Uighur Labor to Produce Face Masks”, 19/07/2020, The New York Times, available on : … Continue reading. The Uyghur cause, which has been a thorn in Beijing’s side for years, is a significant example of the creation and effectiveness of a transnational advocacy network in the realm of human rights. For instance, Western democracies, just became aware through mainstream media of the exploitation this community based in the Xinjiang region (North-West China) is suffering from. In reaction to this massive and recent mediatization, China is currently facing pressures being exerted by the international community.

How did transnational advocacy made that happen? Are these transmission channels as efficient when it comes to specifically denouncing gender violence against Uyghur women?

This article will first draft a quick presentation of the transnational advocacy networks concept in the field of International Relations, then analyze to what extent these dynamics are currently working out in the case of the inhuman treatments currently inflicted to the Uyghur population, with a particular focus on gender violence and its international resonance. In this sense, we observe that the Uyghur cause has long been ignoring the specific oppression Chinese Muslim women were victims of, only framing international denunciations in terms of “Uyghur population” as a whole. The recent uncovers, revealing a differentiated form of violence based on gender could breathe new life into the struggle led by transnational advocacy networks working for the human rights of the Uyghurs.

Transnational advocacy networks: the “Boomerang effect” as weapon

In a seminal article, scholars Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink identified advocacy networks as “key contributors to a convergence of social and cultural norms[2]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”. First of all, they define networks as “forms of organization characterized by voluntary, reciprocal and horizontal patterns of communication and exchange[3]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”. Advocacy networks are formed by advocates, that is to say those who “plead the causes of others or defend a cause or proposition[4]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”. Keck and Sikkink analyse how these non-state actors – NGOs, local organizations, academic researchers, intellectuals… – achieve the framing of a particular issue on an international scale by creating transnational links and exchanging information. Such networks appear especially when communication between activists and their domestic governments is non-existent or malfunctioning. Therefore, according to Baumgartner: “A transnational advocacy network includes those actors working internationally on an issue, who are bound together by shared values, a common discourse, and dense exchanges of information and services[5]Jones Baumgartner, “Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems”, 1991, Journal of Politics, 53, pp. 1044–74.”.

These exchanges are motivated by the will to change policy norms, both domestically and internationally. Indeed, these “political entrepreneurs[6]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.” believe that international conferences are a privileged arena to voice domestic claims and denunciation. For instance, they have emerged during the 19th century though an international campaign for the abolition of slavery. Even though, in the end, not all transnational advocacy networks happen to be efficient, their role is deeply increasing at the international level as they became significant actors in international politics.

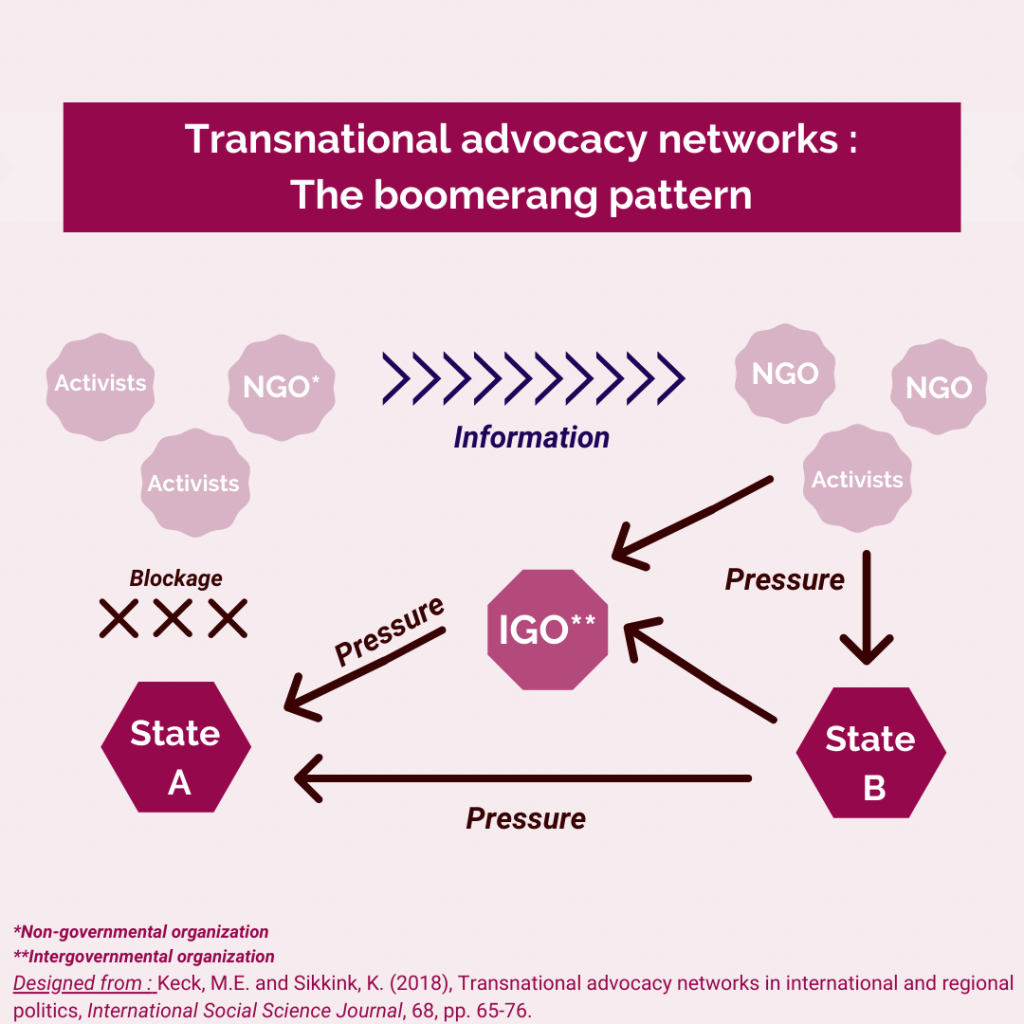

As a matter of fact, Keck and Sikkink coined the “Boomerang pattern[7]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”, a mechanism which describes how transnational advocacy networks work out in an effective strategy. As summarized in a simplified way by the diagram below, interactions between transnational actors seem to follow the same routine, creating solid networks. Indeed, in a scenario where the leaders of State A, supposedly the “the primary ‘guarantors’ of rights[8]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”, happened to be “among their primary violators[9]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”, domestic non-state actors defending human rights – NGOs, activists … – would be given no choice but to resort to “international connections[10]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”, as they are facing a blockage with State A’s government . In order to change “state’s [A] behaviour[11]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.”, they would seek the help of international non-state actors by sharing information with them. In doing so, they would reach a wider public and gain a greater visibility to raise awareness about the violation they are denouncing. International NGOs, using this information would then be able to pressurize State B so that he makes State A stop the violation of human rights. The ultimate goal is to bypass State A in policy making.

Making Uyghurs visible in the international arena

In the case of Uyghur oppression, transnational advocacy networks have proven to be of paramount importance, given Beijing’s lack of openness regarding any kind of denunciation. Indeed, China – starring the role of State A in a “Boomerang pattern[12]Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76.” scenario – is desperately and fiercely trying to sweep domestic protests under the rug. However, Chinese activists and organization managed to reach international actors, those interactions and exchange of information constituting the first step towards international denunciation.

According to scholar Yu-Wen Chen, Uyghurs diasporas played a key role in this process[13]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading, considering Uyghur-issue activists’ main task is “making their issues known outside of China[14]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading”. According to his field study conducted from 2009 to 2010, the most prominent Uyghurs organizations are located in Western Europe and North America. As an example, the Uyghur American Association (UAA) – based in Washington DC – is “active in providing and disseminating information about the Uyghur cause to major news agencies, to international non-governmental human rights organizations and on popular social networking platforms[15]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading”. He observes that Uyghur activists frame their issue in terms of “human rights and the right to self-determination[16]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading” whereas China frames it in terms of “terrorism[17]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading”. This strategy turned out to be effective to a certain extent, thanks to the use of the Internet and Western media. The Uyghur cause was therefore voiced in US Congressional hearings, through diasporas, given Chinese residents difficulties to communicate with the world. Indeed, China reinforced measures to restrain Xinjiang Uyghurs’ access to the Internet.

In 2004 was created the World Uyghur Congress (WUC), gathering several pre-existing organizations, including the UAA, bringing the Uyghur cause for the first time to the international level. Ever since, major NGOs such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) regularly publish cautionary reports shedding light on Uyghur oppression policies led by the Popular Republic of China[18]“Eradicating Ideological Viruses” China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims, September 2018, Human Rights Watch, available on : … Continue reading. In an attempt to get the international community to react, HRW relentlessly voices “more Evidence of China’s horrific abuses in Xinjiang[19]Maya Wang, « More Evidence of China’s Horrific Abuses in Xinjiang”, 20/02/2020, Human Rights Watch, available on : … Continue reading”, that is to say, “the Chinese government’s mass arbitrary detention, torture, forced political indoctrination, and mass surveillance of Xinjiang’s Muslims[20]Maya Wang, « More Evidence of China’s Horrific Abuses in Xinjiang”, 20/02/2020, Human Rights Watch, available on : … Continue reading”. Such accusations were even brought to the UN agenda[21]Stephanie Nebehay, “U.N. says it has credible reports that China holds million Uighurs in secret camps”, 10/09/2018, Reuters, available on : … Continue reading.

In this regard, Chen rightfully considers that the first dynamics composing the “Boomerang pattern” are working out: Chinese non-state actors managed to reach out to transnational advocacy actors who are putting the issue at Western governments’ agenda. However, western democracies have not yet been able to pressurize China in order to make the violence stop. Instead, the Chinese government tends to counter protests by exerting pressure on them, as Chen pointed out[22]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading. As such, transnational advocacy networks denouncing Uyghur oppression haven’t yet come up with a positive outcome.

Besides, the Uyghur cause has long been focused on violence conducted on Muslims Chinese as a whole, thus universalizing the violence committed against both male and female victims. Could gender violence uncovers reinvigorate the Uyghur cause’s international campaign ?

Gender violence: a blind spot in Uyghur transnational advocacy networks?

We observe that the transmission of information about Uyghur oppression has been efficient between domestic and transnational actors. However, for many years, gender violence perpetrated towards Uyghur women has remained silent in the protests voiced by transnational advocacy networks.

Indeed, Western traditional feminist networks have been ignoring the tragedy, whereas Uyghur women are undoubtedly suffering from differentiated forms of violence based on their gender[23]Mathilde Vo, “L’instrumentalisation des femmes Ouïghoures dans la stratégie de domination ethnique des Hans par le gouvernement chinois”, 05/08/2020, Institut du Genre en Géopolitique, … Continue reading. Indeed, not only are they victims of the same inhuman treatments as their male counterparts, but they are also being sexually abused. Some of them are forced to marry Han men, others were sterilized by the Chinese government without even being aware of the surgery they suffered from[24]« Stérilisations forcées de femmes ouïghoures : “Je savais ce qui m’attendait si je refusais’’ », 21/07/2020, France 24, available on : … Continue reading. In short, insofar as they are procreators, women are on the front line when it comes to eliminating an ethnic group through birth control – one of the five criteria defining genocide according to the United Nations[25]Adrian Zenz, Sterilizations, IUDS , and mandatory birth control: the CPP’s campaign to suppress Uyghur birthrates in Xinjiang, June 2020, The Jamestown foundation, available on : … Continue reading.

Nonetheless, being the first victims of a massive policy of extinction conducted towards the Uyghur ethnic group did not propel these women to the forefront of the protests. As a matter of fact, the Uyghur cause has long been focused on denunciations regarding concentration camps, arbitrary arrests and religious repr

ession policies[26]Laurence Defranoux, «Ouïghours : les camps secrets du régime chinois », 29/08/2018, Libération, available on : … Continue reading. The attempts to shed light on gender violence against Uyghur women only took the path draft by the “Boomerang pattern” since 2019 and more significantly since 2020. Rushan Abbas, a Uyghur American activist and former Vice President of the Uyghur American Association (UAA) organized in March 2018 the “One Voice One Step” Uyghur Women’s movement, a demonstration which took place in 14 different countries and 18 different cities. She intends to mobilize women rights’ movement, blaming Western feminists networks for “ignoring the tragedy[27]Rushan Abbas, “Uyghur Women Persecuted: Will the Feminists Support Them?”, 18/08/2020, Bitter Winter Magazine, available on : … Continue reading”, while “Uyghur women are raped, compelled to marry Han Chinese, detained in the dreaded transformation through education camps, and killed[28]Rushan Abbas, “Uyghur Women Persecuted: Will the Feminists Support Them?”, 18/08/2020, Bitter Winter Magazine, available on : … Continue reading”.

In addition, sinologist Adrien Zenz published in June 2020 a compelling study uncovering Beijing’s criminal birth control policy[29]Adrian Zenz, Sterilizations, IUDS , and mandatory birth control: the CPP’s campaign to suppress Uyghur birthrates in Xinjiang, June 2020, The Jamestown foundation, available on : … Continue reading. Edifying evidence is piling up : in 2018, 80% of IUDs installed on Chinese women were in Xinjiang, a region which only represents 1.8% of the population; and in 2019, a county in Xinjiang planned to sterilize 34% of women of childbearing age in one year[30]Laurence Defranoux, « Ouïghours : l’entrave aux naissances, un critère de génocide », 20/07/2020, Libération, available on : … Continue reading.

Western media immediately took up the case, relaying the testimonies of Uyghur women who had been the victims of the Chinese government’s violence. The tone used aims to arouse emotion, as the focus is put on personal testimonies[31]Mathilde Vo, “L’instrumentalisation des femmes Ouïghoures dans la stratégie de domination ethnique des Hans par le gouvernement chinois”, 05/08/2020, Institut du Genre en Géopolitique, … Continue reading. For instance, on 20th of July 2020, French newspaper Liberation headlined “Uyghurs: “I was made to lie down and spread my legs, and I was inserted into an IUD[32]Translated from : Laurence Defranoux, « Ouïghours : «On m’a fait m’allonger et écarter les jambes, et on m’a introduit un stérilet », 20/07/2020, Libération, available on : … Continue reading” on its front page, advertising an “unpublished story[33]Translated from : Laurence Defranoux, « Ouïghours : «On m’a fait m’allonger et écarter les jambes, et on m’a introduit un stérilet », 20/07/2020, Libération, available on : … Continue reading”.

Concerning feminist organizations, nascent action is tangible, notably concerning the “Colleuses” movement. These Feminist activists have recently displayed their support for the Uyghur cause and denounced China’s genocidal policy on the walls of the Chinese embassy in Paris and several France-based Chinese companies[34]“Les Ouïghours soutenus par “les colleuses” sur les murs de Paris”, 30/07/2020, Huffpost, available on : … Continue reading.

Conclusion

To sum up, we observe that the “Boomerang pattern” transmission of information channels seem to be working out quite well for the Uyghur cause as a whole[35]Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : … Continue reading. Yet, when it comes to gender violence against Uyghur women, there is still a long way to go. Either war, regarding undifferentiated oppression or gender-based differentiated oppression, “little action [is] holding Beijing accountable[36]Maya Wang, « More Evidence of China’s Horrific Abuses in Xinjiang”, 20/02/2020, Human Rights Watch, available on : … Continue reading” so far, as rightly pointed out by major NGO Human Rights Watch.

The challenge for the Uyghur struggle, could be the transformation of this China-based gender violence into a broader international issue. Following Rushan Abbas’ praise[37]Rushan Abbas, “Uyghur Women Persecuted: Will the Feminists Support Them?”, 18/08/2020, Bitter Winter Magazine, available on : … Continue reading, the cause could truly use the Feminists transnational advocacy networks’ help to pressurize Western governments and the UN into coercing China to stop abuses conducted towards the Uyghur ethnicity. Indeed, in doing so, Uyghurs defenders could use new transmission channels, reach new advocates and public, opening the path to an efficient “Boomerang pattern”…

To cite this publication : Manon Cassoulet-Fressineau, “Gender violence towards Uyghur women : where does transnational advocacy stands?”, Gender in Geopolitics Institute, 31.08.2020.

References

| ↑1 | Muyi Xiao, Haley Willis, Christoph Koettl, Natalie Reneau and Drew Jordan, “China Is Using Uighur Labor to Produce Face Masks”, 19/07/2020, The New York Times, available on : https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/19/world/asia/china-mask-forced-labor.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑3, ↑4, ↑6, ↑7, ↑8, ↑9, ↑10, ↑11, ↑12 | Margaret E. Keck and Kathryn Sikkink, “Transnational advocacy networks in international and regional politics”,2018, International Social Science Journal, 68, pp. 65-76. |

| ↑5 | Jones Baumgartner, “Agenda dynamics and policy subsystems”, 1991, Journal of Politics, 53, pp. 1044–74. |

| ↑13, ↑15, ↑16, ↑17 | Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : https://gmtp.gmu.edu/publications/gmtpwp/gmtp_wp_12.pdf |

| ↑14, ↑22 | Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : https://gmtp.gmu.edu/publications/gmtpwp/gmtp_wp_12.pdf |

| ↑18 | “Eradicating Ideological Viruses” China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims, September 2018, Human Rights Watch, available on : https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/09/09/eradicating-ideological-viruses/chinas-campaign-repression-against-xinjiangs |

| ↑19, ↑20, ↑36 | Maya Wang, « More Evidence of China’s Horrific Abuses in Xinjiang”, 20/02/2020, Human Rights Watch, available on : https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/02/20/more-evidence-chinas-horrific-abuses-xinjiang |

| ↑21 | Stephanie Nebehay, “U.N. says it has credible reports that China holds million Uighurs in secret camps”, 10/09/2018, Reuters, available on : https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-rights-un/u-n-says-it-has-credible-reports-that-china-holds-million-uighurs-in-secret-camps-idUSKBN1KV1SU |

| ↑23, ↑31 | Mathilde Vo, “L’instrumentalisation des femmes Ouïghoures dans la stratégie de domination ethnique des Hans par le gouvernement chinois”, 05/08/2020, Institut du Genre en Géopolitique, available on : https://igg-geo.org/?p=1720 |

| ↑24 | « Stérilisations forcées de femmes ouïghoures : “Je savais ce qui m’attendait si je refusais’’ », 21/07/2020, France 24, available on : https://www.france24.com/fr/20200721-st%C3%A9rilisations-forc%C3%A9es-de-femmes-ou%C3%AFghoures-je-savais-ce-qui-m-attendait-si-je-refusais |

| ↑25, ↑29 | Adrian Zenz, Sterilizations, IUDS , and mandatory birth control: the CPP’s campaign to suppress Uyghur birthrates in Xinjiang, June 2020, The Jamestown foundation, available on : https://jamestown.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Zenz-Internment-Sterilizations-and-IUDs-UPDATED-July-21-Rev2.pdf?x69018 |

| ↑26 | Laurence Defranoux, «Ouïghours : les camps secrets du régime chinois », 29/08/2018, Libération, available on : https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2018/08/29/ouighours-les-camps-secrets-du-regime-chinois_1675335 |

| ↑27, ↑28, ↑37 | Rushan Abbas, “Uyghur Women Persecuted: Will the Feminists Support Them?”, 18/08/2020, Bitter Winter Magazine, available on : https://bitterwinter.org/uyghur-women-persecuted-will-the-feminists-support-them/ |

| ↑30 | Laurence Defranoux, « Ouïghours : l’entrave aux naissances, un critère de génocide », 20/07/2020, Libération, available on : https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2020/07/20/l-entrave-aux-naissances-un-critere-de-genocide_1794804 |

| ↑32, ↑33 | Translated from : Laurence Defranoux, « Ouïghours : «On m’a fait m’allonger et écarter les jambes, et on m’a introduit un stérilet », 20/07/2020, Libération, available on : https://www.liberation.fr/planete/2020/07/20/on-m-a-fait-m-allonger-et-ecarter-les-jambes-et-on-m-a-introduit-un-sterilet_1794798 |

| ↑34 | “Les Ouïghours soutenus par “les colleuses” sur les murs de Paris”, 30/07/2020, Huffpost, available on : https://www.huffingtonpost.fr/entry/les-colleuses-soutiennent-les-ouighours-sur-les-murs-de-paris_fr_5f2288e2c5b6a34284b6d0a1 |

| ↑35 | Chen Yu-Wen, « Who made Uyghurs visible in the international arena ?”, June 2010, Global Migration and Transnational Politics, Working Paper no. 12, pp 14, available on : https://gmtp.gmu.edu/publications/gmtpwp/gmtp_wp_12.pdf |