The European Union, a cure for the pandemic of violence against women?

09.08.2020

Written by Sophie Bonnetaud

Translated by Kaouther Bouhi

The exceptional measures following Covid-19 made it possible to highlight the extent of violence against women within the European Union. The latter had already been listed in 2014 thanks to a study conducted by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. However, despite these alarming numbers[1], this phenomenon is not perfectly known, as women victims rarely seek help from authorities. Moreover, the European Union contains very few binding provisions specifically dedicated to the struggle against gender-based violence. Nonetheless, it tends to develop its skills and overcome the obstacles caused by States still reluctant to legislate in this area.

The exceptional measures taken in the context of the current global pandemic of COVID-19 made it possible to highlight the domestic and gender-based violence perpetrated against women. Indeed, the United Nations jointly called on States around the world to take urgent measures to ensure peace in households[2]. In fact, according to UN experts, several countries reported a dramatic increase in domestic violence, because of the respect of containment measures which resulted in reduced police response and limited access to emergency and legal services[3].

The European Parliament believes that violence against women is both a violation of human rights and a form of gender-based discrimination[4]. They were defined as “any acts of violence or threats directed at women, and causing or capable of causing [them] harm, physical, sexual, psychological or economic distress, including (…) coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of freedom, in public or private life[5]». Thus, these violences encompass gender-based violence against women, that is to say all violences directed against a woman because of her gender, and domestic violence, meaning “any act of physical, sexual, psychological or economical violence [occurring] within the family or household or between former or current spouses or live-in partners, regardless of whether the perpetrator of the acts of violence is sharing or has shared the same home as the victim[6]”. These violences would arise from existing inequalities between men and women. The latter being regarded as particularly vulnerable because of their gender.

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN: ALARMING NUMBERS WITH NO ADEQUATE LEGAL RESPONSE

An alarming and uncertain increase

Violence against women can take many forms. Harassment, psychological, physical, and sexual violence, sexual mutilations, forced marriages and sterilizations are but a few examples[7]. The French branch of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights published in 2014 a study, regarded as the most comprehensive study ever undertaken on the subject[8]. 42 000 women over the age of 15 years from 28 member States were therefore interviewed. According to this survey, more than one in two women (55%) had been victims of sexual harassment at least one time in their life since the age of 15[9] and almost one in three women had been sexually assaulted. Furthermore, 43% had been victims of psychological violence and controlling behaviors in the context of a romantic relationship[10]. Other studies that were previously conducted have also led to alarming numbers. Indeed, Eurostat reportedly considered that more than half of the victims of murder committed within the EU, are women that have been killed by a sexual partner or a family member[11]. In 2013, a study conducted as part of the “Daphne Project[12]” concluded that 3 500 deaths would happen each year as a result of domestic violence, more than nine individuals per day, including seven women, in all of the EU member States[13].

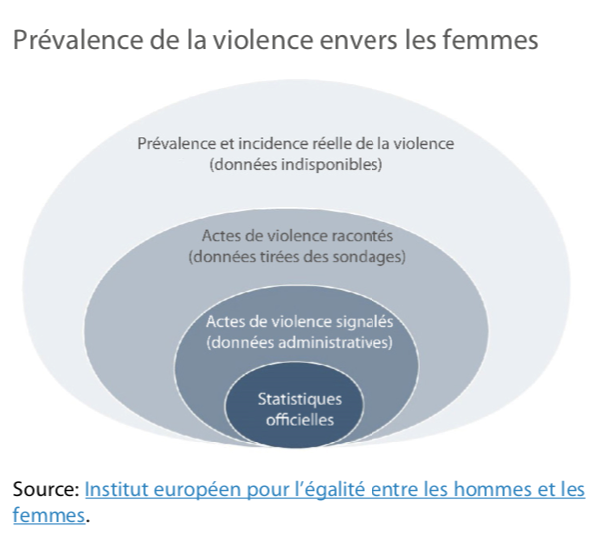

However, even though these numbers are alarming, they do not reflect the exact extent of these crimes. In one hand, the study carried out by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights recounts that only 14% of women living in an EU member State seek help from authorities and testify[14]. The study considers that shame, fear and lack of trust in authorities are the three main factors justifying this lack of reporting[15].

In another hand, the limitation of the samples involved in the study does not allow to reach all women, or the ones victims of less common crimes, such as sexual mutilations[16]. Finally, the research at a European level are hardly achievable as a common definition to all the different EU member States does not exist[17].

Scattered and uncoordinated legal responses

What does international law say?

To contain the phenomenon, the United Nations addressed the issue quite early. Indeed, the organization adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 1973. However, it is the 1990’s that will be particularly fruitful in terms of measures against violence perpetrated against women.

Violence against women is one of the critical areas identified by the Beijing Platform for Action, adopted at the 4th World Conference on Women in 1995. Two years earlier, in 1993, the United Nations had adopted the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. The Committee on the Status of Women, a committee responsible for assessing progress in the implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Programme, and the position of reporter on violence against women, were created. These arrangements have improved the existing legal framework, and to come to the same conclusion : the main problem regarding the struggle against violence against women lies in the inadequate transposition and application of non-binding standards taken at international level within national legal orders.

The Council of Europe quickly addressed the issue. Indeed, in 2002, the Committee of Ministers invited the States to take necessary preventive and repressive measures regarding violence against women, and the protection of victims. The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence that came into force in August 2014 is the first binding legal instrument adopted on the European continent on the matter. All the EU member States have signed it, only 21 of them have ratified it[18].

What about EU member States’ legislations?

To fight against violence against women, many common trends in States’ policies have been observed. Domestic and sexual violences perpetrated against women are the two most sanctioned forms of criminality in the EU[19]. Only some countries, such as the United Kingdom or Italy, looked at the criminalization of other less frequent offences, but no less serious, such as feminine sexual mutilations or crimes of honor[20].

Nonetheless, there is no joint action at a European level yet to address violence against women. Some States consider that the victim’s complaint is necessary to initiate a prosecution[21]. Low prosecution and conviction rates are the main common problem between States. In response, some States, such as Spain or the United Kingdom, established special courts to judge the perpetrators of violence against women[22].

EU ACTION ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN: THE DRIVING FORCE BEHIND THE MEMBER STATES

The existing legislative framework on violence against women

EU law, through its general provisions, prohibits violence against women. Indeed, Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union[23] upholds the principle of gender equality, and of non-discrimination, the rights to dignity and equality are, by contrast, guaranteed by the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union[24]. Finally, Article 8 of The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[25] affirms the political will of member States to fight against all forms of domestic violence[26]. These provisions can serve as a basis to fight against violence against women.

Violence against women are, however, treated by the EU in some binding legal acts in the areas where women are particularly at risk of being subjected to violence (mainly in the context of the struggle against human trafficking[27] or the protection of victims who suffered a crime occurring on the European territory[28]) or when the violence has a cross-border dimension[29]. Besides, the EU has set up legal instruments to recognize orders of restriction or bans of entering the territory of the different member States, so that women can be protected in the entire EU territory[30].

Many national action plans, regarding whether all forms of violence, or specifically the ones perpetrated against women, have been set up in the EU[31]. These action plans focus on preventive measures and advocate the establishment of awareness programs, of training of professionals in contact with victims, of support measures, with the establishment of shelters or telephone helplines for women victims of such violences[32]. Nevertheless, the so-called reintegration programs, such as the access to affordable housing, to employment and training, to income support are less common, yet they are necessary when women decide to leave the marital home where they are subjected to all these violences[33].

Today, the EU does not have any binding legal instrument specifically for containing the phenomenon of violence against women. As a matter of fact, the EU’s competence to create breaches is limited, and cannot intervene in all areas it wishes[34]. Thus, the EU does not apprehend the global phenomenon of violence against women.

The strengthening of policies regarding violence against women

When it comes to violence against women, the European Parliament has the appearance of a precursor, with the adoption of a resolution on the subject on 11 June 1986. Since then, it plays a particularly active role in the area, mainly thanks to the Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality, created following a proposal prepared by a member of the European Parliament, Yvette Roudy in 1979, that will then be supported by the then president of the European Parliament, Simone Veil[35]. This committee has made it possible to create a working group on violence perpetrated against women, in order to establish a strategy at a European level on this subject[36].

Since 2009, the Parliament is trying to put together a global directive opposition on the prevention and the struggle against all forms of violence against women. Its resolution of 25 February 2014 has also made it possible to as the Council to add violences against women to the list of particularly serious forms of crime[37], and to join the Istanbul Convention of the Council of Europe[38]. On 13 June 2017, the EU signed the Convention. The next step being the formal adherence by ratification, a step that depends on the approval of the European Parliament and the member States[39]. However, the ratification of the Convention is blocked by six Eastern European countries: Bulgaria, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, and Czech Republic. These countries consider that the values conveyed by the Convention go against their own beliefs, and the role that the woman should play in these countries, who consider her as being socially inferior[40].

Yet, a directive from the European Union would have far more significant and compelling effects in the member States than the mere membership to the Istanbul Convention[41]. These two measures would enable women to move in a free, secure and fair European space, where violence against women would be prohibited both theoretically and practically, the latter largely lacking in the EU member States[42].

The EU has also been promoting many funding programs granted to States so that they can finance action plans and establish measures aimed at fighting violence against women. Indeed, the 2008 economic crisis has had severe consequences on the subject, causing mainly the closure of numerous shelters[43]. Thereby, thanks to the “Daphne III” program, implemented from 2007 to 2013, member States had access to a budget of more than 116 million euros, specifically dedicated to the funding of projects for the fight against violence against women[44]. Since 2014, the “Rights, Equality and Citizenship” program, implemented from 2014 to 2020, provided for a budget allowance that has been multiplied by two by providing more than 250 million euros to member States. The next program “Rights and values”, will be implem

ented in 2021, to last until 2027. The budget has not yet been determined and will be subjected to a proposal of the Committee[45].

In order to design and develop an effective strategy at a European level, the collection of precise data and figures is necessary. This is the reason why the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE), has started many projects in the area of violence against women, by synthesizing data collected by law enforcement, health services and social services[46]

Conclusion

The EU must draw attention to certain specific forms of violence against women, such as human trafficking, female and forced prostitution, forced marriages and sexual female mutilations. Those are issues present in Europe and which receive too little attention. Women belonging to particularly vulnerable groups because of their social exclusion must also be heard and share their experience. These include undocumented migrant women, asylum-seekers and refugees, as well as women and girls with disabilities or LBTI (lesbian, bisexual, transgender and intersex), or Romani. In this regard, the European Network of Migrant Women asks for the creation of programs of support, protection, and reintegration, as well as the training of professionals of migrant shelters.

The development of violence against women is worrying. With such a high rate of violence, member States must not be the only ones to legislate in the area. If no further action is taken, 3,500 women’s voices will be lost again. The EU must then become a driving force in this area. The harmonization and application of a coherent strategy on the whole European territory is now necessary[47]. However, the election of Ursula Von der Leyen, the first woman president of the European Executive, paves the way for the promotion of gender equality and to a comprehensive and effective action by the EU. This strategy will be supported by Vera Jourova, and by the Gender Equality Commissioner, Helena Dalli[48] and was started on 5 March 2020, the day where the European Commission proposed a new strategy to promote gender equality, with a chapter on violence against women[49]. In this regard, the Commission recalls that, “even though the EU is a leading global player when it comes to gender equality and that it has made significant progress over the past decades, violence and sexist stereotypes still exist : within the EU, one in three women has already been subjected to physical and/or sexual violence[50]”. It remains to be hoped that these measures will be effective and manage to contain, even to a modest extent, a still alarming situation in 2020.

Sources

[1] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, “Violence against women : an EU-wide survey – Results at a glance”, 5 March 2014, Available on : https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra-2014-vaw-survey-at-a-glance-oct14_en.pdf [2] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, « Joint statement by the Special Rapporteur and the EDVAW Platform of women’s rights mechanisms on Covid-19 and the increase in violence and discrimination against women », 14 July 2020, Available on : https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=26083&LangID=E [3] Ibid. [4] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [5] Ibid. [6] The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, opened for signature on 11 May 2011 and came into force on 1 August 2014. [7] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [8] Ibid. [9] Rossalina Latcheva, « Sexual Harassment in the European Union: A Pervasive but Still Hidden Form of Gender-Based Violence », 2017, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol. 32(12) : 1851-1852. [10] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [11] Ibid. [12] Elise Lambert, « On vous explique pourquoi l’assassinat de la journaliste maltaise Daphne Caruana est devenu une affaire d’Etat », 22 December 2019, Franceinfo, available on : https://www.francetvinfo.fr/monde/europe/daphne-project/. [13] Alexandra Gaglione, « ‘Ecoutez aussi l’Europe’ : Le combat de l’UE pour protéger les victimes de violences domestiques », 5 January 2019, Taurillon, https://www.taurillon.org/ecoutez-aussi-l-europe-le-combat-de-l-ue-pour-proteger-les-victimes-de : Croatia was not taken into account as it was not an EU member at the time of the study. [14] Ibid. [15] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [16] Ibid. [17] Ibid. [18] Germany, Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Spain, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Sweden. [19] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [20] Joanna Goodey, « Violence against women: placing evidence from a European Union-wide survey in a policy context », 2017, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Vol.32(12) : 1760-1791 ; Amnesty International, “Crimes of honor », available on : https://www.amnesty.be/veux-agir/agir-localement/agir-ecole/espace-enseignants/enseignement-secondaire/dossier-papiers-libres-2004-violences-femmes/article/4-6-les-crimes-d-honneur : « So-called honour crimes include violence or murder (typically) of women by a family member or a family connection (including partners) in the name of individual or family honor ». [21] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [22] Ibid. [23] This treaty was signed on 7 February 1992 and came into force on 1st November 1993. [24] This convention was adopted on 7 December 2000 but was not binding until the Lisbon Treaty came into force in 2007. [25] This treaty was signed on 25th March 1957 and came into force on 1 January 1958. [26] Ibid. [27] Directive 2011/36/UE of the European Parliament and the Council of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JAI and directive 2004/81/CE on the residence permit of third-country nationals that are victims of human trafficking or of action to facilitate illegal immigration who cooperate with the competent authorities. [28] Directive 2012/29/UE on the rights and protection of victims of crime, Directive 2011/99/UE on the European Protection Order in criminal matters and Rule (UE) n° 606/2013 on the mutual recognition of protection measures in civil matters. [29] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [30] Alexandra Gaglione, « ‘Ecoutez aussi l’Europe’ : Le combat de l’UE pour protéger les victimes de violences domestiques », 5 January 2019, Taurillon, https://www.taurillon.org/ecoutez-aussi-l-europe-le-combat-de-l-ue-pour-proteger-les-victimes-de [31] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [32] Ibid. [33] Ibid. [34] Ibid. [35] Yvette Roudy, « Simone Veil ne sera plus là pour aider les femmes », 1 July 2017, Le Monde, available on : https://www.lemonde.fr/mort-de-simone-veil/article/2017/07/01/yvette-roudy-simone-veil-ne-sera-plus-la-pour-aider-les-femmes_5154063_5153643.html. [36] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [37] This list appears on Article 83§1 of the TFEU. [38] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [39] Ibid. [40] Vincent Georis « L’Europe veut criminaliser toute violence contre les femmes », 5 March 2020, L’Echo, https://www.lecho.be/economie-politique/europe/general/l-europe-veut-criminaliser-toute-violence-contre-les-femmes/10212627.html [41] Alexandra Gaglione, « ‘Ecoutez aussi l’Europe’ : Le combat de l’UE pour protéger les victimes de violences domestiques », 5 January 2019, Taurillon, https://www.taurillon.org/ecoutez-aussi-l-europe-le-combat-de-l-ue-pour-proteger-les-victimes-de [42] Martina Prpic and Rosamun Shreeves, « Violence against women in the EU : State of play”, September 2019, European Parliament, available on : https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2018/630296/EPRS_BRI(2018)630296_EN.pdf [43] Ibid. [44] Ibid. [45] Ibid. [46] Ibid. [47] Alexandra Gaglione, « ‘Ecoutez aussi l’Europe’ : Le combat de l’UE pour protéger les victimes de violences domestiques », 5 January 2019, Taurillon, https://www.taurillon.org/ecoutez-aussi-l-europe-le-combat-de-l-ue-pour-proteger-les-victimes-de [48] Vincent Georis, « L’Europe veut criminaliser toute violence contre les femmes », 5 March 2020, L’Echo, https://www.lecho.be/economie-politique/europe/general/l-europe-veut-criminaliser-toute-violence-contre-les-femmes/10212627.html [49] Ibid. [50] European Commission, Press release on « Gender Equality Strategy: Striving for a Union of equality », 5 March 2020, available on : https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/fr/ip_20_358.

To quote this article : Sophie Bonnetaud, “The European Union, a cure for the pandemic of violence against women?”, 09.08.2020, Gender in Geopolitics Institute.