Cyberactivism: a mobilizing force that is revolutionizing female activist commitment

Illustration : Yona Rouach @welcome_univers

05.11.2020

Written by Louise Jousse

Since the consecration of the Internet as a place of information, gathering, divergence, and daily scandals, feminism seems to go through a rebirth phase. More and more feminist initiatives are being created and shared on social media, especially to raise awareness on gender equality issues and it gives to different movements. Actor Emma Watson’s speech at UN Women in 2014 for the launch of the He For She campaign is a good example since it has been shared many times on Facebook and Twitter. This campaign was successful, including outside of traditional feminist circles. More recently, in 2017, the #BalanceTonPorc movement, was launched by Sarah Muller, a French woman, in order to denounce the sexual harassment that women experience in the workplace. Shared more than 850 000 times in seven months[1], the hashtag became even more popular following the launch of the #MeToo movement, created by African-American activist Tarana Burke, before being popularized by Alyssa Milano on social media.

Nevertheless, these two initiatives are different, one was launched by the very institutional United Nations Organization, the other launched by a solo activist, but they have a common goal: to denounce sexist practices and violence. If these two examples are amongst the most well-known nowadays, there still are a multitude of other less known movements, including in the most repressive States towards women’s rights and freedoms. These movements also vary in their goals: some ambition to denounce practices while others try to raise awareness on one particular cause. This analysis will focus on the new feminist activist practices that arose thanks to cyber tools. We will talk about how feminist cyber activism[2] transforms the activist commitment.

Women’s presence on the Internet

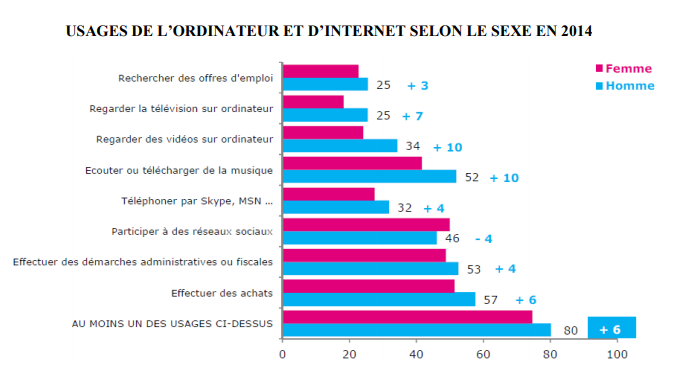

In 2015, an information report on the use of cyber tools by women in France[3] written by French deputy Catherine Courtelle reveals that four out of five women use the Internet and social media. So, women occupy a certain part of the web, given that 49% of Internet users in France are women. However, men and women do not use them in the same way. According to a study by the Center of research for the study and observation of living conditions (CREDOC), there is a “slight gender effect on the uses of the Internett[4]“.

Use of the computer and the internet according to gender in 2014

As the graph above shows, men are more present in cyber entertainment and video games, when women are more active on social media (+4 points) and on blogs, where half of six million blogs are held by women in France[5]. If at first, themes linked to the private sphere such as cooking, beauty and children, etc. were the main topics of these blogs, social and political issues such as gender equality are now growing and reaching more women on the Internet. A British study revealed that the median age for feminist activists is 27, and that 70% of them think that using the Internet has been essential to social movements[6]. In fact, the Internet is seen as a participative space where one can share ideas with others, “allowing a renewal of debates, different ways of participating in politics, which creates a fertile ground for the emancipation and empowerment[7] [8] » of women, who take into their own hands more and more social issues.

The appropriation of the Internet: a struggle and emancipation issue

“The cyberspace is a great space for women’s and men’s emancipation; it can be a tool for new modes of mobilization and expression.”, Clémence Pajot, director of the Centre Hubertine Auclert.

The Internet was developed in the 1980s with the idea of making many voices heard, and to encourage a pluralism of broadcast and creation. For Fabien Granjon, a French sociologist, the appropriation of the Internet is being made to activists’ ends[9]. The Internet then appeared as a means to connect all feminists on the planet in order to promote gender equality, by allowing members of the same association to exchange about their shared interests. From then on, more and more websites are created, from blogs to specialized websites.

It is the case in France with the website Les Pénélopes, created in 1996 following a protest for the right to birth control and abortion which saw 40,000 people take to the streets[10]. Regretting that this protest was not covered by the main media at the time, journalist Joëlle Palmieri and journalist and author Dominique Foufelle decided to create Les Pénélopes website to cover the news from a feminist point of view[11], becoming trailblazers. Reminiscing, Joëlle Palmieri explains that “the Internet is a weapon for feminists[12] ” and that “information and communication technologies systematically remain a goal to reach for women[13] ». Their goal is to create a new public space where women can speak up and express themselves freely, without fear. The public space extended to a virtual space, particularly at a time when women are under-represented and/or suffer sexist violence in the public space.

In order to reach this ideal, Les Pénélopes provided an introduction to IT manual[14] on their website, so that women could become familiar with this tool and develop their own space, at a time when cyber tools were mainly used and developed by men. The Les Internettes website, created in 2016, has allowed the promotion of female creation on the Internet, which has grown exponentially since women have been taking hold of the space. This approach is entrenched in an empowerment process.

What is interesting about feminist cyber activism?

- Between individual and collective action

On the Internet, all topics are exploited, by many means and many people. People expressing their opinions online do not need to be overly politicized, and are often just driven by a certain sensibility that pushes them to expressing them. In fact, many different points of view are broadcasted through different forms: blogs, tweets, Facebook and Instagram posts. The #BalanceTonPorc and #MeToo movements illustrate that fact and count many extremely personal posts by women who shared their experiences of sexual harassment on social media. These testimonies have grown considerably, leading to the opening of a case and then trial against American movie producer Harvey Weinstein, where he was sentenced to 23 years in jail.

These two movements also gradually opened the extent of their denunciations: it was not only about sexual harassment at work, every kind of sexual violence that women can experience throughout their lives. These individual actions soon became collective. Very rapidly, in France, this collective action built around testimonies was anchored in civil society, especially through the creation of the #NousToutes collective, founded in July 2018 by activist and political woman Caroline de Haas and feminist activist Camille Bernard. The collective has organized many gatherings and marches in around 50 cities to denounce sexist and sexual violences[15], more particularly about some appointments to the French government of members whose behaviors and positions were judged incompatible with feminist policies. So, from a simple individual action with a testimony, a collective and organized movement emerged. De facto, the “I” of the testimony became a powerful tool. For Véronique Nahoum-Grappe, a French anthropologist, “these narratives born out of the solitary ‘I’, glided towards the ‘me too’ and ‘her too’ and another one, which depict a ‘we’ in the end’[16] ». The testimony represents a common and powerful practice of online activism[17].

- Cyber activism as a new practice in the political action toolbook

The Internet created a new form of activism, more informal, characterized by activists that do not belong to a political party or association as much[18]. Although not politically assigned, there is an activism that is being built by the broadcast of information using cyber tools. This activism relies on a distanced and freed commitmen[19]. For French sociologist Jacques Ion, “to the commitment symbolized by a stamp on a card to be renewed follows a commitment symbolized by a Post-It note, removable and mobile: making oneself available from time to time and being able to cancel it at any time[20] ». It would then be a temporary activist commitment, which does not mean that activism is coming to an end, but rather that it evolved, allowing the development of cyber activism.

The Internet is used as a new medium of activism allowing it to renew its range of collective actions, a notion developed by American sociologist Charles Tilly, who defines it as “a limited series of routines that are learned, shared and executed through a mostly deliberate process of choice[21] ». One has to understand that it exists through different means of action such as petitions, strikes and gatherings, etc.

As a tool and a medium, the Internet allows to raise awareness to one or several causes through posts on social media or podcasts along the lines of “Les couilles sur la table”, a French podcast that focuses on masculinity from a feminist point of view. Microblogging is also a very efficient tool: many Tumblr and Instagram pages were and are created to highlight the sexism that women experience in their daily life. In this way, the Tumblr page Paye ta Schnek (2012-2019) was created with the aim of compiling women testimonies to raise awareness on harassment in the public space. Followed by more than 40,000 people, it found its audience and unite around a common idea.

Furthermore, the Internet abolishes geographical and physical borders, and thus reaches a larger audience, filling a void left by the traditional media[22]. Nevertheless, the use of IT tools also highlights other borders[23] : one has to take into account variables such as age or language.

- Using the Internet to shine a light on a cause…

The Internet and social media are also used to highlight causes and social movements that had been ignored until then. This past few years, many hashtags appeared on social media to defend and give visibility to a cause. It was the case for a “Stop abortion” project of law by the Polish government in September 2016 to restrict the access to abortion, access that was already limited because only possible if the life of the mother was threatened, if the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, or if the fetus was not viable, making Poland one of most restrictive European countries on abortion.

The political party Razem (“the Left Together”) invited Polish women to protest and to go on strike on October 3rd 2016 to protest and stop this law by not working and wearing black clothes. Under the name Czarny Protest (« the black march »), the movement was relayed on social media with the hashtag #CzarnyProtest. This movement crossed borders and came to France where a support gathering was organized by the collective “Nous d’Abord” in front of the Polish embassy in Paris on October 2nd, 2016[24]. If the Polish parliament eventually abandoned this project, the Polish constitutional court produced a legal act on October 22nd, 2020 that judged unconstitutional the recourse to abortion in case of fetus malformation[25].

Another example, the hashtag #NonENormaleCheSiaNormale (“it is not normal that it is normal”) was launched in 2018 by Italian deputy Mara Carfagna to denounce violence against women during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. The movement soon went viral. The hashtag found political and institutional support in the person of the President of the European Parliament, Antonio Tajani, who took part in the campaign by sharing an image of him with a red mark representing a bruise under his eye on Twitter.

Screenshot from Twitter of Antonio Tajani calling out violence against women

- … and gain results

For a few years now, photos illustrating the concept of manspreading are appearing on social media. The word manspreading is used to denounce men who have a tendency to spread their legs while sitting in public transport, leaving less room for their female neighbors. This behavior is not new (Colette Guillaumin studied how men and women sit in public since the 1990s), but denouncing it on social media has allowed to make it a society issue. Sometimes violently criticized, posts denouncing manspreading are shining a light on a real political problem of domination of men over women[1]. Some town halls have taken the problem into account, such as in Madrid, where posters were set up in public transport following a petition on Change.org by the collective “Mujeres en Lucha[27] ».

In the Northern Macedonia Republic, activist Ana Vasileva launched a new social movement on social media in January 2017 with the hashtag #СегаКажувам (#ISpeakUpNow) with the goal of denouncing the sexual harassment that women experience through testimonies[28]. This initiative grew so much that the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, the Ministry of Education and Sciences and the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Prime Minister have given their support to the movement and set up a hotline for victims of sexual harassment.

These examples show how important these movements have become in the past few years thanks to cyber tools, and show a new form of activism that gathers more people, called “distanced activism[29] », a notion theorized by Jacques Ion. These movements have a real impact on reality and allow to highlight true social issues: street harassment, sexual aggressions, etc.

Critisism against distanced activism

“Activists used to be defined by their causes, today they are defined by their tools”, says Malcolm Gladwell, a journalist at The New Yorker[30].

Despite all of that, distanced activism on the Internet is sometimes criticized, most notably under the term “slacktivism”. Slacktivism denounces supporting a cause through simple actions, without being completely and concretely committed to changing things. Some see it as comfortable and weak activism, that does not ask for a huge commitment like joining a protest or an association. If liking and sharing a post on social media only takes seconds, retweeting and liking content still allows to relay and get more visibility to the activist speech, as Cat Jones explains in her article “Slacktivism and the social benefits of social video: sharing a video to ‘help a cause’[31] ». Highlight and visibility given to a movement through distanced activism still allow to raise awareness. Armelle Weil, a Swiss political science PhD student at the University of Lausanne explains that the Internet “has a major role of presenting and activating consciences and communities, helps in getting people engaged and mobilized[32] ». To sum it up, spaces of socializing between women, such as the Internet, helps in sharing experiences and awaking feminist conscience.

It is not about opposing physical commitment (going to gatherings, join a feminist collective, donating) and distanced activism that Jacques Ion mentions, but about putting them in parallel, since one does not prevent the other. On the contrary, the two forms of activism have become complementary. Indeed, online feminism and offline feminism reinforce each other, through enlarging the public space to the Internet. Women find a new space where they can express themselves, when in traditional media, they are not sought after. De facto, the Internet then appears as a “space of reactivation of the convergence of struggles, all the more valuable that feminism has been, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, blamed for distracting workers from the real struggle (for the emancipation of the working class[33] ».

Conclusion

Feminist cyberactivism is on the rise and renews feminist activist practices, without creating a rupture, but a continuity of physical commitment. The Internet creates a new space where activists can express themselves and give visibility to their movements. The Internet transforms feminist activist practices by bringing a new vision of their demands, and giving a place for activist to speak. Cyber tools have a place in activism and women have known how to use them to defend their interests. Nevertheless, although feminist activists made this space their own to educate, raise awareness and campaign, they still have to face online violence and cyber bullying.

According to a 2015 report by the United Nations Commission[34], 73% of women have seen or experienced online violence in one way or another. This was the case in France with “La Ligue du LOL” (“The LOL League” a group of men on social media) accused of bullying several feminist activists such as Valérie Rey-Robert, author of the book Une culture du viol à la française (“Rape culture, the French way”). If the Internet allows to open the public space and create a new mobilizing force, feminist cyber activists are still facing the same problems than feminist activists did before the Internet, and some people are trying to turn these tools against them, through cyber bullying, a violence recognized as such by European international law.

Sources

[1] MULLER, Sandra, #BalanceTonPorc, Edition Flammarion, page 12.

[2] Here we will say feminist cyber activism to talk about feminist activism online, in reference to the first conference organised about the links between gender, feminist activisms and cyber tools organised by the Centre Hubertine Auclert (a French feminist center for gender equality) in 2015 “Women and tech, cyber activism and feminism”

[3] Information pour la délégation aux droits des femmes et à l’égalité des chances entre les hommes et les femmes sur le projet de loi pour une République numérique, par la députée Catherine Coutelle, 2015 REGIS

[4] PICOT, Patricia, Etude du CREDOC, La diffusion des technologies de l’information et de la communication dans la société française, 2014

[5] TOUTAIN, Ghislaine, expert working at the Fondation Jean Jaurès, a European Fondation of progressist studies, Les femmes à l’assaut du numérique, 2014.

[6] AUNE, Kristin, REDFERN, Catherine, Reclaiming the F World: The New Feminist Movement, Zed, 2013.

[7] The notion of empowerment is a process of emancipation, through which a group of people acquires the tools to strengthen their ability to act.

[8] BERTRAND, David. « L’essor du féminisme en ligne. Symptôme de l’émergence d’une quatrième vague féministe ? », Réseaux, vol. 208-209, no. 2, 2018, pp. 232-257.

[9] GRANJON, Fabien. « Les répertoires d’action télématiques du néo-militantisme ». Le Mouvement Social n°200, nᵒ3 (2002) : 1132.

[10] 8 mars info, « Des milliers de femmes manifestent pour défendre leurs droits », 8 mars info, http://8mars.info/des-milliers-de-femmes-manifestent-pour

[11] PARMIERI, Joëlle, « Révéler les féminismes sur le Net », Femmes et médias, Université des femmes de Bruxelles, éd. Pensées féministes, numéro 2, 2010 (janvier 2011), pp. 93-98.

[12] PALMIERI, Joëlle, « Les Pénélopes, huit ans d’Histoire féministe », mis en ligne le 29 janvier 2015. Consulté le 13 octobre 2020. https://joellepalmieri.wordpress.com/2015/01/29/les-penelopes-huit-ans-dhistoire-feministe/.

[13] PALMIERI, Joëlle, « Les Pénélopes, huit ans d’Histoire féministe », mis en ligne le 29 janvier 2015. Consulté le 13 octobre 2020. https://joellepalmieri.wordpress.com/2015/01/29/les-penelopes-huit-ans-dhistoire-feministe/.

[14] Online manual: https://veill.es/www.penelopes.org/article-4730.html

[15] Le Monde, « Manifestations contre les violences sexistes et sexuelle : ‘On veut du respect, on n’est pas des objets’ ». Le Monde. Published on November 24th 2018. Read on October 17th 2020. https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2018/11/24/marches-noustoutes-les-feministes-esperent-des-dizaines-de-milliers-de-manifestants-dans-les-rues_5388001_3224.html

[16] NAHOUM-GRAPPE, Véronique, « #MeToo : Je, Elle, Nous », Esprit, vol. mai, n°5, 2018, pp. 112-119.

[17] BERTRAND, David. « L’essor du féminisme en ligne. Symptôme de l’émergence d’une quatrième vague féministe ? », Réseaux, vol. 208-209, no. 2, 2018, pp. 232-257.

[18] LEFEBVRE, Rémi. « Le militantisme socialiste n’est plus ce qu’il n’a jamais été. Modèle de « l’engagement distancié » et transformations du militantisme au Parti socialiste », Politix, vol. 102, no. 2, 2013, pp. 7-33.

[19] ION, Jacques, FRANGUIADAKIS, Spyros, VIOT Pascal, Militer aujourd’hui. Paris, Éd. Autrement, coll. Cevipof/Autrement, 2005, 139 p.

[20] ION, Jacques. La fin des Militants ? Éditions de l’Atelier (programme ReLIRE), 1997.

[21] TILLY, Charles. « Les origines du répertoire d’action collective contemporaine en France et en Grande-Bretagne ». Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire 4, nᵒ 1 (1984) : 89108

[22] VEDEL, Thierry, « L’idée de démocratie électronique : origines, visions, questions. » In Le Désenchantement démocratique, ed. Pascal Perrineau, 243-266. La Tour d’Aigues : Éditions de l’Aube

[23] NEVEU Erik, « 12. Médias et protestation collective », Penser les mouvements sociaux. La Découverte, 2010.

[24] FAUROUX, Virginie. « Manifestation devant l’ambassade de Pologne à Paris contre l’interdiction totale de l’IVG », LCI, Published October 2nd 2016. Read on October 14th 2020. https://www.lci.fr/france/manif-noire-contre-l-interdiction-totale-de-l-ivg-en-pologne-2005673.html

[25] IWANIUK, Jakub. « En Pologne, l’avortement devient quasiment illégal après une décision de justice », Le Monde. Published on October 22nd 2020. Read October 23rd 2020. https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2020/10/22/pologne-le-tribunal-constitutionnel-rend-illegal-l-avortement-pour-malformation-grave-du-f-tus_6057023_3210.html

[26] MORIN, Violaine. « Comment le ‘manspreading’ est devenu un objet de lutte féministe », Le Monde, Published on July 6th 2017. Read on October 16th 2020. https://www.lemonde.fr/big-browser/article/2017/07/06/comment-le-manspreading-est-devenu-un-objet-de-lutte-feministe_5156949_4832693.html

[27] Que la Comunidad de Madrid ponga carteles sobre el Manspreading en el metro : https://www.change.org/p/comunidad-de-madrid-que-la-comunidad-de-madrid-ponga-carteles-sobre-el-manspreading-en-el-metro?source_location=minibar

[28] UN Women, « Dans les paroles d’Ana Vasileva : ‘Non seulement nous participons au débat, mais nous agissons’ ». ONU Femmes. Published on February 27th 2018. Read on October 10th 2020. https://www.unwomen.org/fr/news/stories/2018/3/in-the-words-of-ana-vasileva

[29] ION, Jacques. « V – L’engagement distancié », La fin des Militants ? sous la direction de Ion Jacques. Éditions de l’Atelier (programme ReLIRE), 1997, pp. 79-97.

[30] Quote from the article « Le slacktivisme, un moyen d’éveiller les consciences ou simplement de se donner bonne conscience ? » de Bahia Nar, published on Novembre 25th 2012. Read on October 15th 2020. http://atelier.rfi.fr/profiles/blogs/le-slacktivisme-un-moyen-d-veiller-les-consciences-ou-simplement?xg_source=activity

[31] JONES, Cat. « Slacktivism and the social benefits of social video: Sharing a video to ‘help’ a cause ». First Monday. 20. 2015.

[32] WEIL, Armelle. « Vers un militantisme virtuel ? Pratiques et engagement féministe sur Internet [1] », Nouvelles Questions Féministes, vol. vol. 36, no. 2, 2017, pp. 66-84.

[33] BLANDIN Claire. « Présentation. Le web : de nouvelles pratiques militantes dans l’histoire du féminisme ? », Réseaux, vol. 201, no. 1, 2017, pp. 9-17

[34] “Fight against online violence towards women and girls, a call to raise global awareness”, UN Commission task force on high speed Internet, September 2015.

To quote this article : Louise Jousse, “Cyberactivism: a mobilizing force that is revolutionizing female activist commitment”, 05.11.2020, Gender in Geopolitics Institute.