Interview with Excision, Parlons-en !

12.01.2021

Interview conducted by Lucile Carrouée

Moïra Sauvage is a former independent journalist and an essayist who specialises mostly in women’s rights and violence against women. She was in charge of the women’s commission of Amnesty France, but she was also the president of the network of organisations Excision, Parlons-en !, which fights against female genital mutilations (FGM, also known as excision) in France and in the world. Today, she is still at the core of Excision, Parlons-en !, but she is also the co-president of a network of 39 organisations that fight against sexism in France, Ensemble contre le sexisme.

Violence against women is based on the female gender. They affect women and not men, and they’re based on these preconceived ideas, these stereotypes that societies have about what a woman must be. And when she doesn’t conform, she can experience violence.

Excision is a mutilation of women’s genitals that has always existed: traces of that practice were found on Egyptian mummies, so well before Jesus Christ. The United Nations defined different forms of female genital mutilations, and none of them respect children’s fundamental right to protection from violence. It can be the partial or complete removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy) by cutting it, or the removal of the clitoris and labia minora, but sometimes the labia majora as well. In some cases, after the clitoris has been cut off, the labia are sewn together, and the genitals will only be reopened for the young woman’s sexual relations after she’s married: that’s infibulation.

There are also types of female genital mutilations that are not classified, that we can currently find in Indonesia for example, where excision is only a perforation of the clitoris. But in any case, we are firmly opposed to it, because there is no reason to harm the genitals of girls and women.

GGI: What are the consequences on the physical and mental health of those young girls who are excised?

Indeed, the consequences of excision are numerous. The notable physical consequences are extreme pain, haemorrhage and infections. The victims, and especially babies can die from it, because female genital mutilations most often take place in villages, far from hospitals and health services, without anaesthesia or monitoring. Moreover, when the child grows up, other types of pain can appear, during periods, sex or while giving birth. Those repercussions are often the result of genitals that very often do not heal well, as Doctor Foldes explained to me. He is the “inventor” of the method used to fix the damages of a clitoridectomy, partial or complete removal of the clitoris and excision.

We can’t forget the psychological repercussions. A baby probably won’t have the memory of such a trauma, but a little girl will remember that the people who are supposed to love her most, like her mother, her aunt, her cousin, have harmed her that way. There is also the future consequence of being in pain during sex and not being able to enjoy her sexuality normally and to the fullest.

We’ve seen cases in France of young women who were excised very young and didn’t know that it had happened. They realised that they weren’t like the others while talking to their friends, their partners and by going to gynaecologists and doctors’. That realisation leads to, of course, a lot of questioning, incomprehension and for some, a kind of shame.

So we can’t say that all women live with female genital mutilations the same way. Some will suffer a lot physically; some won’t realise it and it will cause a psychological shock later on. Some will feel the need and the will to build themselves back up, some won’t because they’ve learnt to live with it.

GGI: Is there a geography of female genital mutilations in the world? Is it a scourge that affects all women across the globe with no distinction?

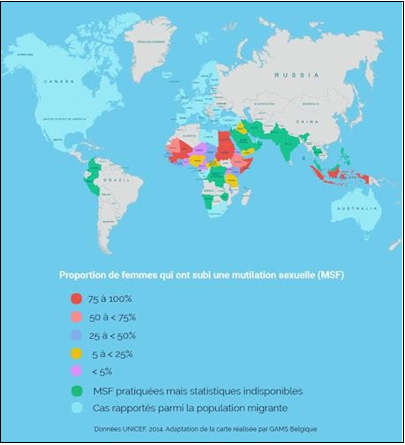

Contrary to what many people may think, especially in France, it isn’t a type of violence that only happens in Africa. We can’t generalise and say that all African women are excised, and that excision only happens in Africa. In West Africa for example, which is the region with which France has the most relations, there are places where these mutilations happen and others where they don’t, and they’re only some tens of kilometres apart. There are tribes in Northern India that excise their daughters, and therefore there are women’s movements that arise to oppose those practices. In Malaysia, there are also a lot of women who are excised.

The founder of Excision, Parlons-en ! is a young journalist who lived in Egypt. He realised that 90% of Egyptian women had gone through female genital mutilations, and that’s when he became aware of the magnitude of this and of the need to talk about it and fight it. Of course, the locals and women had already been fighting against it for a long time. On Excision, Parlons-en !’s website, you can find a map of the countries where excision cases have been identified. There are many of them across all continents.

Moreover, the religion of the populations who practice excision is not only Islam, as many tend to think. In Egypt again, many members of the Coptic church for example are excised. The Coptic church is a Christian church. And as I said before, ancient traces of these mutilations date from before the main monotheistic religions appeared.

Female genital mutilations were also used by French doctors and psychiatrists in the 18th century to calm women’s hysteria. This practice perdured in the Western world until the 1950s, in the United States of America, in psychiatric hospitals where the patients were subjected to all sorts of torture.

In the end, the fact that many people across the world thought of such a violent practice is also horrible.

Female genital mutilations in the world (source: https://www.excisionparlonsen.org/)

GGI: Is excision categorised as sexual mutilations done in times of conflict? Or is it mostly cultural?

It’s mostly cultural, excision is not a crime like rape that we can characterise like weapons during a war. It’s not a religious practice either. Although many families justify it with religion, neither the Bible nor the Quran nor any other religious texts demand that young girls be excised. It really is a practice that is done in a cultural and ritualistic context. There is also a strong fear of “what will they say?”, meaning a fear of societal opinion that pushes women to inflict that on younger women. That’s what we call the sense of social obligation.

With Covid-19 this year, Excision, Parlons-en ! has noted that many young girls weren’t able to go to their home country for vacation, which no doubt allowed many to avoid this type of trauma. However, in many countries that excise women, many young girls weren’t able to go to school because of the pandemic and had to stay in the familial sphere. Unfortunately, there was an increase of cases and a loss of progress linked to girls’ schooling, which helped them with emancipation.

GGI: What are the official measures that are currently in place in international organisations, and do they have a real impact?

Officially, the UN, the African Union and generally international, and sometimes national texts condemn female genital mutilations. It’s good, it’s a start, because those legal tools are important to legitimise the fight and the steps taken by activists on site.

In France, many trials took place between the 1980s and 1990s. Thanks to those trials and the lawyer Linda Weil-Curiel, parents and those who excise are legally punished in France. It becam

e known to immigrant communities, and it caused the application of this act to slow down.

But female genital mutilations are mostly done in villages, and it’s not the same situation. The law seems distant, excisions still take place because it’s a private practice, one that’s done in the privacy of the familial sphere. So it’s harder to control, and we must change the societal norms as well as mindsets.

GGI: How does Excision, Parlons-en ! help women who have been excised?

Excision, Parlons-En ! was created in 2013 to let people know that excision still exists, and in France too, even though the French thought that, after the 1990s trials, it was a distant problem that didn’t exist anymore. Excised women still exist in France and have children, and the main goal was to protect those young girls from potential danger by continuing to alert medias and to talk about it.

Indeed, when a practice isn’t from our culture, we can vaguely hear about it but that doesn’t mean that we know it. We want to educate people and explain what female genital mutilations are. We also lobbied authorities, the government and the Ministry for Women’s Rights, who thankfully listened to us and supported us. Excision, Parlons-en ! organised many colloquiums, discussion groups to talk about this problem and make it known to professionals who might encounter excision victims while doing their jobs, whether they be jurists, doctors, nurses…

Excision, Parlons-en ! is also part of a network called End FGM, based in Brussels. We took part in meetings with people from many countries, and the main goal was to share experiences, ideas and positive actions. We also worked with this network on an online learning tool for professionals. We translated it in French, and it also exists in about ten European languages.

The goal is both to help excision victims, but also to raise awareness on all levels. We try to be closer and closer with people with immigration backgrounds, and we’ve been creating links with organisations of women from diasporas to put them in the spotlight and highlight their experiences. Half of our leading board is made of women of African backgrounds. The idea is to show others that we can fight together against female genital mutilations, whether we are affected by them or not.

If victims contact us directly, our organisation has a gynaecologist who specialises in fixing clitorises and a jurist who specialises in asylum seeking because of excision. We also redirect them to the national federation GAMS, who directly help women on site.

GGI: Why do you think abandoning excision is so difficult?

Excision is part of tradition, and it’s always complicated to abandon a ritual you’ve had for so long. As I said earlier, there’s always this fear of change, this fear that parents of a young girl have of others’ opinions. The goal of female genital mutilation is to prevent women from feeling sexual pleasure, and from being tempted by adultery. Some men refuse to get married to a woman who hasn’t been excised, and it is inconceivable in many places that a young girl is not married.

Moreover, the women who perform excisions are often paid for their actions. That obviously explains why they are the first who don’t want this practice to end. However, there are now new ceremonies where those who excise are still paid, not to excise, but rather do good deeds. This allows for a smoother transition, and one where everybody wins.

In East Africa, we noticed that giving young girls mobile phones allowed them to communicate about the existence of female genital mutilations, their risks and ways to escape them.

GGI: Can we say that, through excision, there is still a persistent drive to control women’s sexuality and body?

Yes, absolutely, and this drive is still very prevalent in our societies. The fear of women’s bodies and pleasure persists. This will to keep a masculine domination is still very strong everywhere in the world, and through various means. We noted that there are actions taken in the countries that practice excision as well as diasporas, and that’s a bit reassuring. A British organisation called Forward (Foundation of Women’s Health Research and Development) led by women of African origin organised a campaign that showed men how female genital mutilations were done with scissors and genitals made out of modelling clay. Of course, their first reaction was horror, which goes to show how ignorant men are on this issue, and they can barely imagine the potential trauma of it. Even if some men still want their wife to be excised so that she won’t cheat, we noted that young men want to have a full sex life and share its pleasure with their partner.

GGI: What advances have you noted since the organisation was created in 2013?

There are positive advances, in France at least. It’s a subject that governments have seized, since they understood that female genital mutilations also affected young French girls with immigration backgrounds. We talked about it a lot, there have been awareness campaigns in schools that have led to great progress today. Our current campaign Alerte Excision has, in my opinion, touched a lot of people. We’ve developed it in the span of three years and it spread well, through posters but also through modern communication such as chats.

We always want to make sure that our words and our campaigns don’t fall into ill-meaning hands. Unfortunately, there are always people who want to demonise some communities, especially immigrant ones, and who are always looking for new ways to criticise them even more.

GGI: Changing mentalities is vital, but it’s not enough. Who are the other actors who must fight against female genital mutilations?

Many organisations act to change mentalities, by going on site, to take the time to meet with women and explain the dangers of excisions, for their health and their daughters’. But I think that men also have a role in this. If families continue to think that their daughter will never get married if she’s not excised, then there is little chance that things will change. Men also need to learn how to distance themselves from tradition, they need to know more about excision and be willing to contribute to change. And men usually only listen to other men, so some of them need to join women in the fight against female genital mutilations. But it’s not easy…

In terms of governments, if they wanted to invest a bit more money in campaigns against excision, they probably could. Invest in instructors who would teach different people, in schools, in hospitals and others is still a possibility to change mentalities on the long term.

But excision is often thought of as a private thing, and governments don’t feel like it’s their business. Many think that they shouldn’t get into the lives and choices of families, just like domestic violence. It’s an argument used to avoid of solving the problem. It doesn’t help that this issue is about sexuality, women’s sexuality. It is a phenomenal taboo that still makes a lot of people too uncomfortable to address publicly. Hence the importance of advocacy and lobbying to pressure governments.

GGI: What are the next actions that Excision, Parlons-en ! plans on doing?

For a few years we’ve been preparing special events for the 6th of February (International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation). We are supported by the government, some ministers are coming, the press is talking about it, and we’re organising it with diasporas.

After that, we don’t have anything that’s perfectly defined. Recently, we’ve reorganised the leading board of our organisation, and we’ve been working on it. But our main goal is still awareness, we want to collaborate with the Ministry of National Education to make training courses in schools. We

’ve already done a few, but they were occasional, at the request of some schools. Ideally, it should be done more regularly and organised, with the approval of the National Education. As for our Alerte Excision campaign, however, this should be its last year.

GGI: What is the best we can do to fight against excision in France?

The first people who can act are those who are at the centre of this issue, the families. Then, the professionals who might meet excised women, who could act concretely in their jobs. However, for people who don’t have any particular links to female genital mutilations but who still want to support this cause and its victims, they must be as informed as possible and talk about it. We can’t forget them. Maybe also sign up on social medias of organisations like Excision, Parlons-en ! who fight against excision, to know about the advances and be there at potential actions.

To cite this article : “Entretien avec Excisions, Parlons-en !”, 12.01.2021, Institut du Genre en Géopolitique.