Obstetrical and gynaecological violences in West Africa between activist fight and development issue.

18.09.2020

Written by Marion Luc et Noumidia Bendali Ahcene

Translated by Kaouther Bouhi

The question of obstetrical and gynaecological violences in West Africa is the subject of growing attention from many different people. National and International institutions like the activist field seize this question together in order to offer a holistic answer to this problem, suitable to the specific cultural context of this region.

1. A map of obstetrical and gynaecological violence[1].

From 2016 to 2018, with a study led by the Lancet about mistreatments during childbirth, the World Health Organization collected data about 3 countries of West Africa and one from South-Est Asia : Nigeria, Ghana, Guinea and Myanmar. This study revealed that a third of women[2] met in those countries suffered from physical and verbal violence or were victims of discrimination during their delivery. The study also warns on the abnormally high rate of vaginal inspection done without the consent of the patient[3].

The World Health Organization identifies seven classes of mistreatments which can happen during gynaecological consultations and obstetric acts which contribute to deface and dehumanize the quality of the treatments for the patient. Those are:

- Physical abuse (resort to force);

- Sexual abuse;

- Verbal abuse (threats, mocking);

- Discrimination and stigmatization (based on gender, ethnic group, age);

- Disrespect of the professional standards (negligence, infringement of privacy);

- Bad relation between nurse and patient;

- Pressure linked to the health care system (lack of fundamental equipment)[4].

The sub-region of West African is faced with the manifestations of those types of abuse because of external systemic factors that we will talk about later. The accumulation of those different factors puts women who are already confronted to this in a position of high vulnerability.

2. How can we explain that violence ?

- An unbalanced link between a nurse and a patient.

“The primordial mechanism which can explain the abuses suffered, is the systematic difference of “cultural capital” and “symbolic capital” between nurses and patients. And the larger the differential, the more risk there is that the patient suffers from abuse. Even if she is rich or poor, supported or not[5].” – Jean-Paul Dossou[6]. Those notions of cultural and symbolic capital appeal to Pierre Bourdieu’s theory, which involves at the same time a will of the subjects to inquire, but also the possibility to do so or not[7]. That’s why the age, but also social class, disability, and of course, gender of the patient are central factors, which determine the link between the nurse and the patient. In fact, those different features can have a negative influence on the patient’s capacity to trust, which helps them better negotiate different actions with the healthcare personnel.

The disequilibrium in the relationship between nurse and patient is also increased by the maternal death rate. The African Union, United Nations Economic and Social Commission of Africa and the Corporate Council on Africa indicate that maternal death rate for the sub-region of West Africa is 564 for 100 000 live births[8], which is largely higher than the global average, which is 216 for 100 000 live births[9]. But this number covers different realities between countries, in fact, the lowest maternal death rate can be seen at Cabo Verde (42 for 100 000 live births), whereas Sierra Leone has the highest rate (1380 for 100 000 live births)[10]. Those numbers remain on the whole extremely high and are themselves a factor of stress which can constitute a form of trauma.

“It’s very common to say about a woman during the period of labour that she has one foot in the grave. (… ) So she surrenders herself to the nurse.[11]” The risk of not surviving labour can put women in a state of vulnerability. Jean-Paul Dossou even speaks about an abandoning to the nurse, who is “considered a demigod[12]”. It is this disequilibrium that constitutes a favorable situation to violence.

- Poor working conditions of the healthcare personnel.

As we said above, the World Health Organization recognized the pressure linked to the health system, as the lack of equipment, proper hygiene conditions and enough trained personnel, as a form of abuse[13]. In the case of the sub-region of West Africa, two elements seem to have significantly damaged the working conditions of healthcare personnel. On one side it is the so-called cleanup policies imposed by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and on the other side the devaluation of the CFA franc. Following those measures, salaries fell from at least 50%, causing frustration from the health care personnel.

Works from Yannick Jaffré and Olivier de Sardan (2003) speak of a “behaviour problem” from the nurses regarding their patient. The inherent problem of the healthcare system in those countries, like the lack of equipment and recognition of the work of the personnel, can lead to situations of corruption from them. They tend to privilege certain patients compared to others, depending on economic criteria[14].

This is shown by a journalistic study carried out in different hospitals of Lagos, which emphasises the central problem of the access to decent labor services: the social class of the people who give birth. In fact, public hospitals, that usually deal with deplorable sanitary conditions, are mainly used by the poorest part of the population. This economic precarity is usually accompanied by poor levels of education and information about their rights and health. Those factors of precarity accentuate the vulnerability of the patient during their labor and contribute to legitimising physical acts of abuse or verbal from the healthcare personnel[15].

- The influence of traditions.

The weight of traditions and cultural norms on the access to quality gynaecological and obstetric treatments is especially brought to light by an article of Gender in Action for the case of Senegal. It says that the gynaecological consultation can constitute a first form of violence for some people, because certain traditions insist that according to certain religion and culture, women are not allowed to undress in front of strangers[16]. They are usually confronted to the refusal to be consulted by their husband or partner. Thus, the consultation can be seen as a transgression. However, cultural norms usually forced customs qualified as “honourable” or as a source of dishonour linked to labour.

Florence-Marie Sarr Ndiaye, a retired Senegalese midwife, talks about it : « In our culture, a woman must not cry during her labour. It is a matter of honour, for her and for her family. Before, as a woman soaked in the culture of my country, I usually repeated to the mother-to-be to calm, to be quiet.[17]”. Those norms constitute a denial of the pain that can be felt by women during their labour because they are incapable of expressing it. In that case nurses are less able to help with the pain in the best way, because on one side it is not explicitly stated and on the other side they can also be caught up in stereotypical representations and judge the patient’s feelings.

Finally as we said before, the question of the cultural and symbolic capital of the people involved during the gynaecological and obstetric act is central. That’s why a study of Lancet shows that teenagers and young women report to have suffered from mistreatment during their labour more than their older counterpart

s[18]. In fact, teenagers and young women reported verbal abuse and degrading treatments towards them because of the judgment from the healthcare personnel on their sexuality, which usually is still considered as a taboo[19].

3. What solutions for a “positive experience of childbirth” ?

- Advice from the WHO

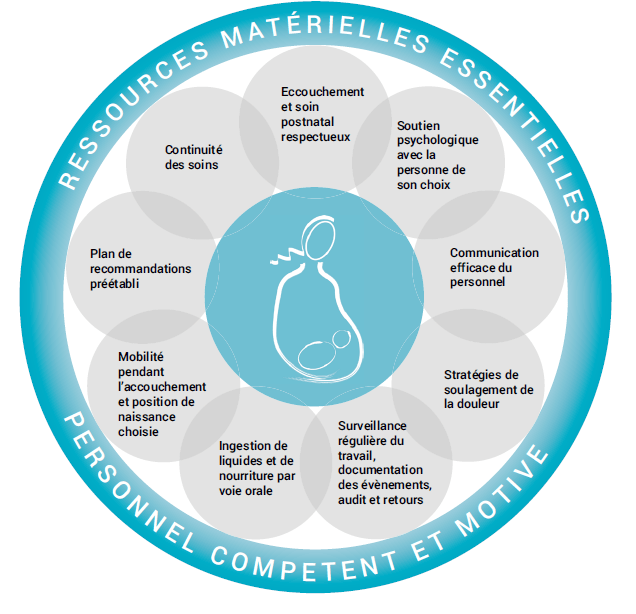

In their document Recommandations de l’OMS Sur les soins intrapartum pour une expérience positive de l’accouchement Transformer le soins des femmes et des nourrissons pour améliorer leur santé et leur bien-être, the WHO offers an infographic on the different essential actions in order to improve the obstetric handling of women and thus guarantee respectful and non violent services[20] :

From the top, clockwise : safe childbirth and post-natal care ; psychological support ; efficient personal communication ; strategies to ease pain ; regular monitoring of labour, documenting events, consulting and feedbacks ; ingestion of liquids and food orally, mobility during labour and choice of the position of delivery ; pre-established recommandation plan ; continuity of care.

This holistic approach allows not only to deal with the question of physical abuse, but also a decent handling of the pain and communication on the different acts, but also on the psychological angle, like psychological support during labour and correct information before and after it.

Those recommendations are also important, because they deal with an empowerment process of the patient. For example, securing the possibility for the person to choose the position in which they want to give birth contributes to the responsibilisation of women in their healthcare, allowing to reduce the unequal relations between patient and nurse.

- Legal recognition at regional level.

Finally, the importance of the legal recognition of the act of gynaecological and obstetric abuse can secure a system of punishment for mistreatment. On the 23rd of October 2019, the Charter of the Respectful Maternity Treatment[21] sees the light of day during the regional African forum on the experience of treatments. This document has ten articles which recognize the right to see their quality of the treatments secured.

Even if it is not a restrictive legal tool (it is not an international agreement signed by several member States), this charter marks a first step towards the human rights tied to maternity. In fact, it is an interesting tool that can be used as a lever of advocacy with the governments. It allows women and parturients to have a legal tool to demand the acknowledgment of their rights.

This charter does not constitute the only action established to improve the gynaecological and obstetric handling of women. It must be followed by concrete change, as Blami Dao[22] emphasises. It is necessary to think about the physical organization and the labour rooms, in order to guarantee more privacy and more humane conditions for patient and nurse[23].

Conclusion:

The sub-region of West Africa is not exempt from the occurrence of acts of obstetrical and gynaecological violence. After the addition of this problem to the international political agenda around the world, a lot of quantitative and qualitative data was being collected and relayed about those phenomena in West Africa. The activist field and national and international institutions seem to seize the problem and be together in order to research sustainable solutions in order to put an end to this mistreatment. In order to impulse change and a sustainable enhancement of treatments, it is important to work on transforming the logistical aspects (infrastructure, tools), the law and finally, the practices. It will bring to a realization from the nursing auxiliaries, who will be more able to practice in a healthy environment, but also in a favourable atmosphere to the decision taking of the patient on their gynaecological and obstetrical healthcare.

Sources

[1] In this article, we are going to define obstetrical abuse by Marie-Hélène Lahaye’s definition: the addition of two types of violence : institutional abuse and abuse based on gender”, characterized by “all behaviour, act, omission or abstention committed by the health care personnel, which is not justified medically and/or which is performed without clear consent by the pregnant woman or the parturient”. The term of gynaecological abuse deals with ; the act or sexist words, of shame or physical abuse that can be suffered by people during gynaecological consultations.

[2] In this work, the term “women” will concern all the people considered as women by the health care personnel, however all of the women considering themselves as women but who can be denined in their identity par them (cisgender women, trangender men, transgender women and nonbinary people).

[3] OMS, Des données récentes révèlent que les femmes sont victimes de mauvais traitements lors de l’accouchement,2019 25th october.

[4] Le Monde, Jean-Paul Dossou : « Payer avant d’accoucher est la première violence faite aux femmes », 2019 25th october.

[5] Le Monde, Jean-Paul Dossou : « Payer avant d’accoucher est la première violence faite aux femmes », , 2019 25th october.

[6] Bourdieu Pierre. Les trois états du capital culturel. In: Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales. Vol. 1979 30th november. L’institution scolaire. pp. 3-6.

[7] Ibid.

[8] L’Union Africaine, la Commission Economique des Nations Unies pour l’Afrique et le Corporate Council on Africa, Taux de mortalité maternelle par pays (2015), 2018.

[9] Leontine Alkema PhD, et al., Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, The Lancet, vol. 387, issue 10017, 2016 30th January.

[10] L’Union Africaine, la Commission Economique des Nations Unies pour l’Afrique et le Corporate Council on Africa, Taux de mortalité maternelle par pays (2015), 2018.

[11] Le Monde, Jean-Paul Dossou : « Payer avant d’accoucher est la première violence faite aux femmes », , 2019 25th october.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Tantchou Josiane, « En Afrique, la matérialité du soin au cœur des tensions soignants-soignés ? », Sciences sociales et santé, 2017/4 (Vol. 35), p. 69-95.

[15] RPmedias, De Blah Elijah, Les violences obstétricales en Afrique de l’Ouest, inégalités sociales ou non ?, 24.11.2014.

[16] Genre en action, Sénégal : gynécologique, une spécialité médicale qui peine à entrer dans les moeurs, 2015.

[17] Le Monde Afrique, Achard, Victoire. Tradition et manque de formation des sages femmes, deux clés des violences de l’accouchement. 2019 23rd october.

[18] A Bohren, Meghan et al., How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: a cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys, The Lancet, volume 394, issue 10210,2019 8th October.

[19] Ibid.

[20] OMS, Recommandations de l’OMS Sur les soins intrapartum pour une expérience positive de l’accouchement Transformer le soins des femmes et des nourrissons pour améliorer leur santé et leur bi

en-être.

[21] White ribbon Alliance, Le respect dans les soins de maternité: les droits universels des femmes lors de la période périnatale.

[22] Professor in gynaecology and technical director of Jhpiego in West and Central Africa.

[23] Le Monde Afrique, Victoire Achard, L’Afrique de l’Ouest adopte une charte des soins de maternité respectueux, 2019 24th October.

Bibliography :

A BOHREN Meghan et al., How women are treated during facility-based childbirth in four countries: a cross-sectional study with labour observations and community-based surveys, The Lancet, volume 394, issue 10210, 8th October 2019. Available on : https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)31992-0/fulltext#seccestitle150

ACHARD Victoire, Jean-Paul Dossou: « Payer avant d’accoucher est la première violence faite aux femmes », Le Monde, 2019, [en ligne], Available on: https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2019/10/22/jean-paul-dossou-payer-avant-d-accoucher-est-la-premiere-violence-faite-aux-femmes_6016451_3212.html

ACHARD Victoire, « L’Afrique de l’Ouest adopte une Charte des soins de maternité respectueux », Le Monde, 2019, [en ligne], Available on https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2019/10/24/l-afrique-de-l-ouest-adopte-une-charte-des-soins-de-maternite-respectueux_6016768_3212.html

BOURDIEU Pierre Les trois états du capital culturel. In: Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales. Vol. 30, November 1979. L’institution scolaire. pp. 3-6, Available on: https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1979_num_30_1_2654

DE BLAH Elijah, Les violences obstétricales en Afrique de l’Ouest, inégalités sociales ou non ?, RPmedias, 24th November 2014, Available on: https://www.rpmedias.com/les-violences-obstetricales-en-afrique-de-louest-inegalite-sociale-ou-non/

Genre en action, Sénégal : gynécologique, une spécialité médicale qui peine à entrer dans les moeurs, 2015, Available on: https://www.genreenaction.net/Senegal-gynecologie-une-specialite-medicale-qui.html

LAHAYE Marie-Hélène, Accouchement, les femmes méritent mieux, 2018, Ed. Michalon, p.187

Leontine Alkema PhD, et al., Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group, The Lancet, vol. 387, issue 10017, January 30th 2016, Available on : https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00838-7/fulltext

L’Union Africaine, la Commission Economique des Nations Unies pour l’Afrique et le Corporate Council on Africa, Taux de mortalité maternelle par pays (2015), 2018. Available on : https://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/Africa-Business-Investment-Forum/2018/maternal_mortality_ratios_fr.pdf

OMS, Des données récentes révèlent que les femmes sont victimes de mauvais traitements lors de l’accouchement, October 9th 2019. Available on:https://www.who.int/fr/news-room/detail/09-10-2019-new-evidence-shows-significant-mistreatment-of-women-during-childbirth

OMS, Recommandations de l’OMS Sur les soins intrapartum pour une expérience positive de l’accouchement Transformer le soins des femmes et des nourrissons pour améliorer leur santé et leur bien-être. Available on : https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272434/WHO-RHR-18.12-fre.pdf?ua=1

TANTCHOU Josiane, « En Afrique, la matérialité du soin au cœur des tensions soignants-soignés ? », Sciences sociales et santé, 2017/4 (Vol. 35), p. 69-95. Available on: https://www.cairn.info/revue-sciences-sociales-et-sante-2017-4-page-69.htm

White ribbon Alliance, Le respect dans les soins de maternité: les droits universels des femmes lors de la période périnatale. Available on: https://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/RespectfulCareCharterFrench.pdf

To quote this article : Marion Luc et Noumidia Bendali Ahcene, “Obstetrical and gynaecological violence in West Africa between activist fight and development issue”, 18.09.2020, Gender in Geopolitics Institute.