Temps de lecture : 6 minutes

References

| ↑1 | Lare Watson, “Women less likely to win major research awards”, Nature, 13/09/21, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02497-4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | EHNE, Encyclopédie numérique d’Europe, Université de la Sorbonne,https://ehne.fr/fr/encyclopedie/th%C3%A9matiques/%C3%A9ducation-et formation/d%C3%A9mocratisations-et-in%C3%A9galit%C3%A9s-scolaires-en-europe/l%E2%80%99acc%C3%A8s-des-femmes-aux-universit%C3%A9s-1850-1940 |

| ↑3 | Françoise Héritier, Michelle Perrot, Sylviane Agacinski, Nicole Bacharan, « La Plus Belle Histoire des Femmes », 2011, p30. |

| ↑4 | Mathilde Larrère, “Rage against the machismo”, 2020, p. 68. |

| ↑5, ↑8, ↑17 | Ibid |

| ↑6 | EHNE, Encyclopédie numérique d’Europe, Université de la Sorbonne, https://ehne.fr/fr/encyclopedie/th%C3%A9matiques/%C3%A9ducation-et-formation/d%C3%A9mocratisations-et-in%C3%A9galit%C3%A9s-scolaires-en-europe/l%E2%80%99acc%C3%A8s-des-femmes-aux-universit%C3%A9s-1850-1940 |

| ↑7 | Agnès Schermann-Legionnet, Simon Paye, et Anne Loison. « Chapitre 13. Les carrières des chercheuses et chercheur·euses en écologie : une comparaison France-Norvège », Sexe & genre. De la biologie à la sociologie, Éditions Matériologiques, 2019, pp. 195-217. |

| ↑9 | Lokman I. Meho, « The gender gap in highly prestigious international research awards, 2001–2020 », Quantitative Science Studies 2021, 2 (3), pp. 976–989. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00148. |

| ↑10, ↑14, ↑18 | Ministère de l’enseignement supérieur, de l’innovation & de la recherche ,“Vers l’égalité femmes-hommes ? : chiffres clés [2019]”, https://archives-statistiques-depp.education.gouv.fr/Default/doc/SYRACUSE/45423/vers-l-egalite-femmes-hommes-chiffres-cles-2019-ministere-de-l-enseignement-superieur-de-la-recherch?_lg=fr-FR |

| ↑11 | Dea Lorenzini, Entretien de la directrice de recherche à l’INSERM de Luminy, Marseille, Laboratoire de neurologie, Novembre 2021 |

| ↑12, ↑19 | Lokman I. Meho, « The gender gap in highly prestigious international research awards, 2001–2020 », Quantitative Science Studies 2021, 2 (3), pp. 976–989. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00148 |

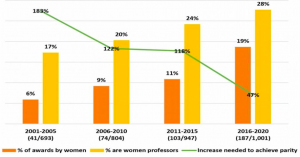

| ↑13 | See graph 2 |

| ↑15 | UNESCO, « Déchiffrer le code: l’éducation des filles et des femmes aux sciences, technologie, ingénierie et mathématiques (STEM) », :https://fr.unesco.org/STEMed. |

| ↑16 | Agnès Schermann-Legionnet, Simon Paye, et Anne Loison, « Chapitre 13. Les carrières des chercheuses et chercheurs en écologie : une comparaison France-Norvège », Bérengère Abou éd., Sexe & genre. De la biologie à la sociologie, Éditions Matériologiques, 2019, pp. 195-217 |