Women’s underrepresentation in parliament: issues and challenges of representative democracy

12.10.2020

Written by Coline Real

Translated by Bianca Wiles

Despite it being strongly challenged, representation remains a democratic regime’s privileged form of expression. It is founded on the idea that the people, who cannot in any practical way exercise their own sovereignty, delegate their governing power to representatives. The right to vote, through which the people nominate these representatives, is therefore a key instrument of representative democracy.

The emergence of modern democracies saw women being denied their status of individuals as citizens, only to be relegated to second class citizenship. Their exclusion from the electoral body was deemed natural. Indeed, in the eyes of certain anthropological perceptions, women are fragile and emotional beings who can easily be manipulated. Sociologically, the family unit’s interest are publicly represented by the head of the household, namely the man[1]. Thus, the “people’s representatives” were in reality only representing the male-land-owning elite.

Women’s delayed access to the right to vote – first in 1893 for Kiwi women, then during the 20th century in a majority of states, and lastly in 2011 for Saudi Arabian women[2] – represented a first step towards an increasingly representative democracy. Their right to vote allowed women to take part in the democratic process, not only allowing them to vote during elections or on the occasion of referendums, but also giving them the possibility to be eligible.

Yet, the introduction of universal suffrage was not entirely helpful in opening assemblies’ doors to women.[3]While they constitute 49.6% of the world’s population[4], women only represent 25% of members of parliament worldwide[5].

Besides this being a clear violation of political equality between men and women, the latter’s numerical underrepresentation in decision making arenas highlights a democratic deficit and undermines the concept of representation. Can we truly argue that female voters are represented when women only constitute a fourth of all representatives?

Linking numerical and substantial representation

While the objective of representation is to make electors – both men and women – present on the political stage, two approaches clash[6]. The descriptive approach, otherwise called standing for, considers that the identity of those elected interferes with their decisions therefore bringing tensions and generating power relations. Here, a democratic institution is only representative when it mirrors society and includes, proportionally, political minorities. In contrast, the substantial approach, or acting for, considers that those elected are chosen to represent the political choices of all electors, their identities having no impact on their position. Elected officials would therefore be representing the entire population and be capable of understand the expectations, needs and interest of a great diversity of people and act for the common good[7].

One of the major criticisms of this liberal vision of representation is that it is blind to the various political identities and the power relations resulting therefrom.

Certain female authors refuse to differentiate these two approaches and support that descriptive and substantial representations are intrinsically linked. In other words, presence and ideas go hand in hand. The underrepresentation of women in democratic institutions leads to their interests being overlooked in decision making. Such numerical underrepresentation in politics is consequently detrimental both to gender equality and to the smooth and efficient functioning of representative democracy.

Women’s presence in governmental assemblies: a prerequisite for representative democracy

The past few years have seen democratic systems strained by a “crisis of representation”. This phenomenon seems to persist in a number of states[8]. It can be explained by the fact that « the sovereign people feel dispossessed of the power given to them by democracy and do not identify with their representatives”[9].

While the feminisation of representation cannot counteract the election’s distinctive principle[10], it reinforces the sense of proximity women have vis-à-vis their female representatives simply due to their shared gender. This identification to women representatives is not linked to any physical attributes but rather to shared lived experiences[11]. This shared experience of marginalisation creates a shared memory that engenders strong feelings of identification and trust[12].

Though this identification takes on a non-negotiable symbolic dimension, this is not its only virtue. It also brings about consequences on the legitimacy of the democratic institution and the decisions it makes. Legislation fighting against gender-based violence will gain legitimacy when adopted by a body constituted equally of male and female representatives, rather than one constituted primarily of men.

According to Anne Phillips, author of The politics of presence, women’s representation calls for, in addition to their institutional presence, the consideration of their “interests” – although the term “women’s interests” must be used with some precaution. The study of the subject has shown some debate around the consistency, or even the existence, of these interest[13]. French political scientist Réjane Sénac questions the asymmetry between the construct of women as an interest group and the lack of any consideration of male specific interests[14].

However, certain issues are only addressed simultaneously to women’s entrance in the political arena. This is what Pippa Norris et Joni Lovenduski demonstrate through their empirical studies based on surveys carried out on British members of parliament, both men and women[15].

The results of these studies showed that on topics of market economy, Europe, and traditions, there are less differences of opinion between men and women than between political parties. On the other hand, when it comes to topics of positive discrimination and gender equality, strong divergences between men and women are observable, and this regardless of political views. Otherwise said, female representatives of all political hues are more preoccupied by issues of gender discrimination than male representatives regardless of their age, education or socio-economic background. Women’s greater concern for issues of inequality and discrimination can be explained by their belonging to a political minority, a group discriminated against.

A second study by the same abovementioned researchers shows that this different positioning between men and women on issues of gender equality within the political elite – read: the representatives – is a reproduction of the same divergences that exist within the “masses”[16] – read: the represented. Institutions’ representativity of women is therefore considerably improved when they are equally composed of men and women.

Women’s election into parliaments redesigns the political agenda, introducing new questions and overturning certain consensuses which had, until then, remained unques

tioned due to the exclusion of certain segments of society[17].

Some nuance is nonetheless necessary. Women’s presence in politics does not automatically create substantive representation. This is due to two reasons. Firstly, women sometimes tend to be more conservative than men on issues of gender equality such as abortion[18].

Secondly, a parliament constituted of 50% of women does not guarantee women’s representation in their socio-economic, cultural, ethnic, religious, and sexual orientation diversity.

It is equally important to avoid any particularistic pitfalls. To claim that women are better represented because they are present in democratic institutions does not necessarily mean that only women can represent women and that female representatives only represent women.

Yet, to enhance representativity in institutions it is vital to increase women’s presence in politics and in particular through mechanisms allowing for the institutionalisation of descriptive representation.

Fighting women’s underrepresentation in parliaments through the institutionalisation of descriptive representation

The sphere of politics remains today a man’s privilege where fratriarchy[19] and sexism persist. Many political and institutional mechanisms impede women’s access to power and consolidate men’s positions, especially through the holding multiple offices, the dignitarification[20] and oligarchy within political parties[21].

To bring down the structural barriers which stop women from accessing politics, American political scientist Jane Mansbridge identified several institutionalisation mechanisms of descriptive representation such as quotas and a proportional system of representation[22].

Quotas

The passive incremental track approach, which came from northern countries and is based on the liberal idea of equal opportunities and involves waiting for cultural, political, social and economic development to slowly create better female representation, constituted the privileged plan of action for a long time. Today many states have switched towards a fast track[23]. The latter constitutes a more active approach, originated in South America and aims to impose quotas in order to obtain better female representation[24].

This approach calls for the adoption of coercive and temporary measures in order to remedy the structural barriers which prevent women from entering the political arena.

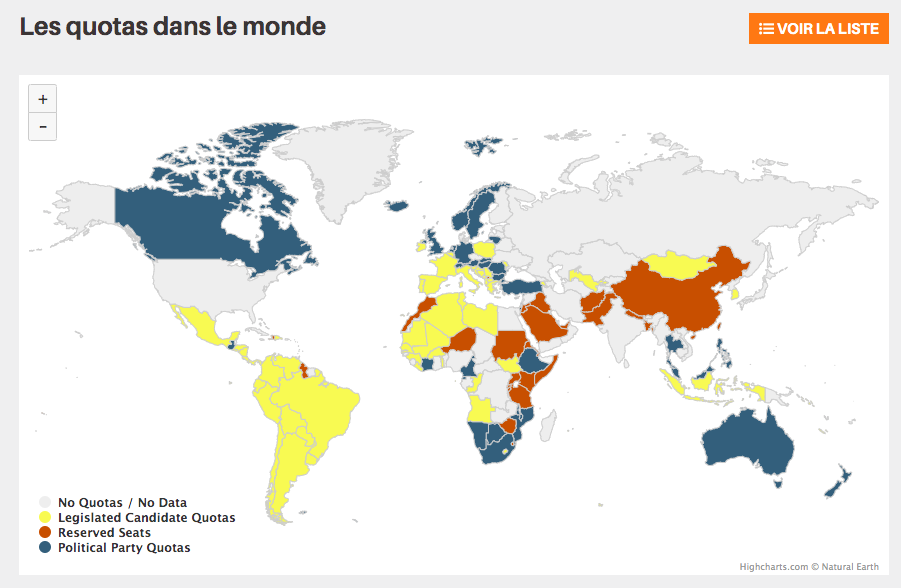

There are three different types of quotas. The first are reserved seats, these are quotas that can be imposed by national legislation of the constitution. Secondly, there are candidacy quotas that can also be imposed by the constitution or by national legislation. Finally, there are party quotas, which are voluntarily adopted by political parties. The latter two quotas set a minimum number of female candidates.

These quotas, in achieving a “critical mass” of women, reshape the lacking democratic system that had until then been unable to include half of its citizens.

However, these devices face some criticism. Firstly, some deny the legitimacy of those women elected under these quotas and deem that their place was not earned on the basis of their capacities but rather of their gender. Secondly, while the quotas are used to attenuate gender inequalities, there is a risk of “institutionalising the differences between men and women at the expense of their equality”[25].

The proportional system of representation

An important correlation exists between the electoral system and women’s representation. In fact, the percentage of female members of parliament tends to increase when there is a proportional system of representation[26]. This is mostly explained through the existence of lists of more than one candidate[27]. “Under a single-member constituency system, the candidate selectors might be reluctant to pick a women as the party’s sole candidate, using the excuse, genuine or otherwise, that they believe some voters will be less likely to vote for a women instead of a man. But when several candidates are to be chosen, it not only is possible by also positively advantageous for a ticket to include both men and women, for an all-male list of five or more candidates is likely to alienate some voters.”[28]

Nonetheless, this proportional system is limited in some ways. This is not a means of sustainably including women in electoral functions. According to Jane Mansbridge, this is not a « flexible » mechanism that would allow for the introduction of descriptive representation as lists of candidates, and the proportion of women therein, can change from one election to the next[29].

Gender Quotas Database of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

Conclusion

Quotas and the proportional electoral system have allowed for the improvement of representativity in democratic institutions as they help women’s elections. Yet, a balanced split of parliamentary seats does not necessarily imply balanced power-sharing.

In fact, despite this institutionalised equality, women in politics are still victims to three exclusion mechanisms, the first one being stereotyped allocation. Women are often reduced to gender-specific qualities and weaknesses such as common sense, sensitivity, and their proximity to the people’s everyday issues,[30]

which often puts them in charge of stereotypically feminine topics.

Such a confinement to these issues implies women’s exclusion from certain subjects seen as rather masculine or subjects needing opposite qualities to those attributed to women. Also, this exclusion is reinforced by the resilience of exclusively masculine groups. According to Clémentine Autain, French member of parliament for the left-wing France Insoumise party, “politics are not confined to parliamentary chambers. It takes place at the parliament’s local bar for example. It is in those moments, when strategy is discussed, that women become invisible. Men stay in contact among themselves; women don’t exist anymore. Women are excluded from the conversations that influence political choices.”[31].

Finally, exclusion happens through intimidation. Numerous sexist and insulting statements and behaviours remind women that they are the odd ones out in politics. The French political scene provides plenty of examples of this. In 2012, then Minister for territorial equality and housing Cécile Duflot took the floor under her male counterpart’s whistling and comments due to the fact she was wearing a floral print dress. In 2013, Véronique Massonneau, member of parliament for Europe Écologie Les Verts, had her speech interrupted in the l’Assemblée Nationale by chicken’s cackles. The political sphere, being no exception to other spheres, also sees instances of sexual violence, harassment and assaults alike.

In line with what has been discussed above, it is important to remind that while claims of equality are based on gender relations rather than race or class relations, ideas of representativity of democratic institutions must imperatively include other political minorities.

Sources

[1] Pierre Rosanvallon, Le sacre du citoyen. Histoire du suffrage universel en France, Gallimard, Paris, 1992, p.267.

[2] For additional information see : « L’ouverture du vote aux femmes dans le monde », in Edouard Pflimlin, « Il y a cent ans les femmes obtenaient le droit de vote au Royaume Uni », 6th of Febuary 2018, Le Monde. Available at : https://www.lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/article/2018/02/06/il-y-a-cent-ans-les-femmes-obtenaient-le-droit-de-vote-au-royaume-uni_5252327_4355770.html

[3] Françoise Gaspard, « Du patriarcat au fratriarcat. La parité comme nouvel horizon du féminisme », 2011, Cahiers du Genre, Volume Hors-Série, Numéro 3, p. 141.

[4] World bank data, year 2019. Available at : https://donnees.banquemondiale.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.ZS?end=2019&start=1960&view=chart

[5] For additional information refer to global and regional averages of the percentage of women in national parliaments, published by the Inter-Parliamentary Union. Available at: https://data.ipu.org/fr/women-averages

[6] Pioneering distinction made by Hannah Pitkin in The concept of representation, University of California Press, Berkley, 1972.

[7] Manon Tremblay, « Représentation » in Catherine Achin and Laure Bereni (dir.), Dictionnaire Genre & science politique : concepts, objets, problèmes, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, pp. 456-468

[8] Examples of the recent Yellow Vest movement in France, of the hirak protest movement in Algeria , or of protests in Colombia and Belorussia.

[9] Michèle Riot-Sarcey, « Démocratie » in Catherine Achin and Laure Bereni (dir.), Dictionnaire Genre & science politique : concepts, objets, problèmes, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, pp. 142-154.

[10] Bernard Manin, in Principes du gouvernement représentatif, Flammarion, Paris, 1995, points out that voters chose their representatives based on their distinctive characteristics they value.

[11] Jane Mansbridge, « Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women ? A Contingent ‘Yes’”, Aug. 1999 The Journal of Politics, Vol. 61, No. 3, pp.628-657.

[12] Melissa Williams citée dans Manon Tremblay, « Représentation », in Catherine Achin et Laure Bereni (dir.), Dictionnaire Genre & science politique : concepts, objets, problèmes, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, p. 457.

[13] See also: Irene DIAMOND and Nancy HARTSOCK, « Beyond Interests in Politics: A Comment on Virgina Sapiro’s ‘When are Interests interesting ? The Problem of Political Representation of Women’ », Sept. 1981, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 75, No. 3, pp. 717-721 ; Virginia SAPIRO, « Research Frontier Essay: When are Interests Interesting ? The Problem of Political Representation of Women », Sep. 1981, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 75, No. 3, pp. 701-716.

[14] Réjane Sénac, L’égalité sous conditions, Presses de Sciences Po, Paris, 2015.

[15] Joni Lovenduski, Pippa Norris, « Westminster Women : The Politics of Presence », 2003, Political studies, Vol. 51, pp. 84-102.

[16] Rosie Campbell, Sarah Childs and Joni Lovenduski, “Do women need women representatives”, Cambridge University Press, 2009, pp. 171-194.

[17] Anne Phillips, The politics of presence, Oxford University Press, New York, 1995, pp.156-158.

[18] Manon Tremblay (op.cit., p. 457) uses the example given by Ronnee Schreiber in Righting Feminism: Conservative Women and American Politics (2008). Women connected to right-wing movements usually oppose abortion on the basis of the danger this medical procedure may cause to women’s health rather than the traditional reason relating to “child murder”.

[19] According to Françoise Gaspard (op.cit., 2011), in the public sphere, « is as if a pact between brothers, the fratriarchy, had taken over from a patriarchy in decline”. In other words, the fratriarchy, where the brother-figure took replaced the father-figure, is another androcentric system of dominance based on male solidarity.

[20] Dignitarification occurs when political power is concentrated in the hands of dignitaries. These are “a small group of individuals and families that accumulate economic wealth (especially land property), social prestige and political power » (Jean Louis Briquet, Notables et processus de notabilisation en France aux XIXe et XXe siècles, 2012. hal-00918922 ; Translated from French).

[21] Bérangère Marques-Pereira, « Quotas ou parité : Enjeux et argumentation », 1999, Recherches féministes, Volume 12, Numéro 1, pp. 103-121.

[22] Jane Mansbridge, op.cit., p. 652.

[23] 13

0 states have imposed quotas, be it constitutionally, during elections or within political parties. See Annex 1.

[24] Réjane Sénac, « Quotas/Parité », in Catherine Achin et Laure Bereni (dir.), Dictionnaire Genre & science politique : concepts, objets, problèmes, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, pp.432-444.

[25] Chantal Mouffe, “Feminism, Citizenship and Radical Democratic politics”, in C. Mouffe (dir.), The Return of the Political, Londres, citée dans Bérangère Marques-Pereira, op.cit.

[26] Among the 20 states with the highest proportion of women in Parliament, 15 of them impose a proportional electoral system (Rwanda, Island, Nicaragua, Sweden, Finland, South Africa, Ecuador, Namibia, Mozambique, Norway, Spain, Argentina, Timor-Leste, Angola, Belgium), 3 have a combined electoral system (Bolivia, Senegal, Mexico), 1 has a majority electoral system (Ethiopia) and 1 has an “other” electoral system (Cuba). For additional information, see: https://data.ipu.org/compare?field=chamber%3A%3Afield_electoral_system&structure=any__lower_chamber#map et https://www.ipu.org/resources/publications/infographics/2017-03/women-in-politics-2017

[27] Mona Lena Krook, “Studying Political Representation : A Comparative-Gendered Approach”, March 2010, Perspectives on Politics, Vol.8, No. 1, p.234.

[28] Michael Gallagher, Michael Laver, Peter Mair (1996) cited in Direction Générale des Études du Parlement Européen, « Incidences variables des systèmes électoraux sur la représentation politique des femmes », 1997.

[29] Jane Mansbridge, op.cit., p. 652.

[30] Grégory Derville, Sylvie Pionchon, « La femme invisible. Sur l’imaginaire du pouvoir politique », Mots. Les langages du politique, 2005/2, n°78, p.62.

[31] Clémentine Autain said this when heard by the High commission on gender equality (Haut Conseil à l’Égalité entre les femmes et les hommes) in the context of the second study on sexism in France: fighting sexism in companies, media and politics (“Deuxième état des lieux du sexisme en France : combattre le sexisme en entreprise, dans les médias et en politique”), in 2020

To cite this article: Coline Real, “Women’s underrepresentation in parliament : issues and challenges of representative democracy”, 12.10.2020, Gender in Geopolitics Institute.